By 1919 the Great War had dragged on for five long blood-soaked years. Even with the USA having

joined the Allies in 1917, victory had been elusive for any of the combatants. For the two years that had

followed that declaration, a flood of war materials had poured from the American industrial heartlands

and onto the awaiting shipping. When the holds were full and the escorting warships summoned,

another of the almost countless convoys made its way east, out into the combative waters of the North

Atlantic.

For three days the forty ships in the convoy had steamed eastward. The merchant ships and their

priceless cargos were shepherded by their Anglo-American escorts, keeping them safe from the German

wolves that still occasionally hunted for such rich prey. That third night, which was now evaporating as

the sun rose, heralded the arrival of a new dawn. The hours of darkness had been quiet and there had

been no interruptions, no hostilities. The convoy’s Commodore crossed another twenty-four hours of

the voyage off in his mind. The sanctuary of Liverpool was a few hundred miles closer than when the sun

had set.

As they had on the previous dawns, with the sun rising above the horizon and the protective shroud of

darkness being dissolved, the lookouts on each of the warships searched the horizon for hostile

shipping. As their shipmates stood ready at their action stations, dozens of binoculars swept the horizon

for vessels sailing under the Imperial Eagle.

Stationed on the convoys port flank, a sailor high in the mast of the British light cruiser HMS Cairo

paused in his current sweep. Through the lenses he tried to discern if that was a smudge of smoke

contaminating the horizon, or if his eyes were only tired. It had been a long cold watch, and a few

seconds earlier his mind had drifted towards thoughts of the galley and then his bunk. But those

thoughts were gone, as he strained to clarify the smudge. Slowly, the cloud grew clearer and as he

struggled to focus; the cloud drifted apart to become two. The two smudges grew both sharper and

larger as he finally accepted what he was seeing. As the clouds continued to grow both slowly and

remorselessly, beneath them he could finally discern two shapes. Shapes that were uninvited,

unexpected, and consequently could only be the intrusive ships of the Imperial German navy.

The port allied escorts turned almost as one to form a barrier between the merchant ships and the

enemy. As the commodore signaled his merchant ships by flag with orders to head south, the starboard

escorts swung 180° to hastily join with their port side compatriots. As they increased speed, the hard

steaming warships passed through the four score of merchant ships now commencing their flight

southward. As the allied force formed what was most likely a futile barrier, the lookouts finally

confirmed the biggest of the two shapes was Imperial Germany’s new Mackensen class battlecruiser, the

Graf Spee. The Admiral knew they were heavily outgunned, but he knew his force of warships could at

least grant the merchant ships time to seek the southern horizon, to slip over it and out of sight. But as

the Graf Spee came on, the second intruder seemed to hold back from her big gunned companion. That

second shape was odd in form. Her deck was flat and only broken amidships by a funnel and an island

structure. As the Graf Spee gun crews launched the first of the mornings 35cm shells at the escorts,

overhead was to be heard the sound of aerial motors. Mid-Atlantic was not the place to hear such

sounds, but finally the escorts Rear Admiral understood who that second intruder was. He knew that themuch debated and feared aircraft carrier, built by the Imperial navy had every intention of sinking the

merchant ships and their priceless cargos. As those first shells splashed amongst the escorts, overhead

five planes bearing the Teutonic cross on their wings, flew unmolested towards the defenseless

merchant ships.

Fiction, yes. But surprisingly based on a realistic possibility.

Prior to 1915, the German navy had (excluding the Zeppelins) dabbled, as had the Royal Navy, with

heavier than air aviation. On the outbreak of war, the 2,425-ton British merchant ship, the SS

Craigronald had whilst conducting her commercial trade, lain moored in the Baltic port of Danzig. She

was immediately seized as a prize of war by the authorities, handed over to the Imperial navy to be

renamed SMH Glyndwr (S.M.H. = Seiner Majestät Hilfsschiff (“His Majesty’s Auxiliary Ship”)). The former

British merchant ship was designated to serve as a seaplane tender. Following a conversion, which was

both simple and quick, she was able to carry four seaplanes housed on newly installed fore and aft

decks, no hangars were included within the work. A large cargo boon had been installed to allow the

seaplanes to be swung out over the side and lowered into the sea. They would, following the flight, be

recovered in the same manner. The Glyndwr was to start her Imperial service as a training ship in the

Bay of Danzig, serving the fledgling Imperial Naval air force as a training craft, with a crew of ninety-one.

Until March 1915, the new SMH was employed in the Gdańsk Bay for pilot and observer training. But

after March she was transferred to Memel were her crew conducted aerial reconnaissance trials against

submarines. But her role was short, being terminated on June 4th, having hit a mine, and suffering

considerable damage that was never fully repaired. From September 1916 she was reduced to a hulk,

before being delivered to the UK on January 21st, 1919, overhauled, and returned to commercial service

as the name Akenside. The ship was scrapped around 1955.

To supplement the Glyndwr, two German cargo ships were also ordered to be converted into seaplane

tenders, both to serve within the Baltic Sea. The SMH Answald and SMH Santa Elena were

commissioned into the High Seas Fleet as Flugzeugschiff I (“airplane-ship”) and II, respectively. Unlike

the Glyndwr, both the ”airplane- ships” were to have hangars built both fore and aft. These could store

between three and four aircraft each. The Answald was fitted with booms both fore and aft. In addition,

she was outfitted to serve as a torpedo boat tender. However, the conversion was quickly established to

be unsatisfactory, and it was not until 1915 that either ship saw active service, following yet further

modifications. However, once they were finally deployed, they contributed to the authority of the

German Baltic Fleet, working to keep the Russian navy on the back foot.

The ex-British freighter SS Oswestry, which had also been taken as a prize in August 1914, (and renamed

Oswald), was to be converted in 1918 to the role of aircraft tender and attached to the IV Torpedo Boat

Flotilla. The Oswald could operate four two-seater float planes, the Friedrichshafen FF 29s.

In addition to the “airplane ships,” the cruiser SMS Friedrich Carl had in 1914, been fitted with two

aircraft. But soon after, she was sunk by a mine and the aircraft were never to be deployed.

On January 15th, 1915, a Flugzeugbau Friedrichshafen FF 29 was to have the distinction of being the first

aeroplane to be launched from a submarine, the U12. The unarmed scout aircraft was secured to the U-

boat’s forward deck and on her maiden flight piloted by the Zeebrugge naval airbase commander

Oblt.z.S. von Arnauld de la Perrière. The U-boat’s bow was submerged after the seaplane had been

unsecured, and de la Perrière successfully launched his craft skywards. But the Imperial Navy observers

present were unimpressed, and a decision was made not to use U-boats in such a manner again. In

addition, the battlecruiser Derfflinger, the light cruiser Medusa and several Sperrbrecher (“barrier

breaker”)made successful use of aircraft, as did the armed merchant cruiser SMS Wolf.

In Wilhelmshaven, the German Admirals were finally coming to understand the potential of shipborne

aircraft. They were as a result to order the construction of seaplane tenders, each with the ability to

maintain station with the High Seas Fleet. Two cruisers (SMS Roon and Stuttgart,) were also ordered to

be surrendered to the dockyard for conversion. Work was begun on the Stuttgart on January 21 st , 1918,

at the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven and on May 16th she was to be commissioned as an ‘aircraft

carrier’. Two large hangars had been fitted aft of her funnels, with the capacity to store two seaplanes. A

third aircraft was carried on the roof of the hangars. Stuttgart was, once recommissioned, to provide air

cover for minesweeping operations within the North Sea, but she was never used in an aggressive

mission and was to be employed later within the Baltic. The Roon was never to be completed.

Even though the Stuttgart now offered the potential of an aircraft tender that could keep pace with the

High Seas Fleet, her three aircraft was simply too few machines to meet with a fleet’s needs at sea.

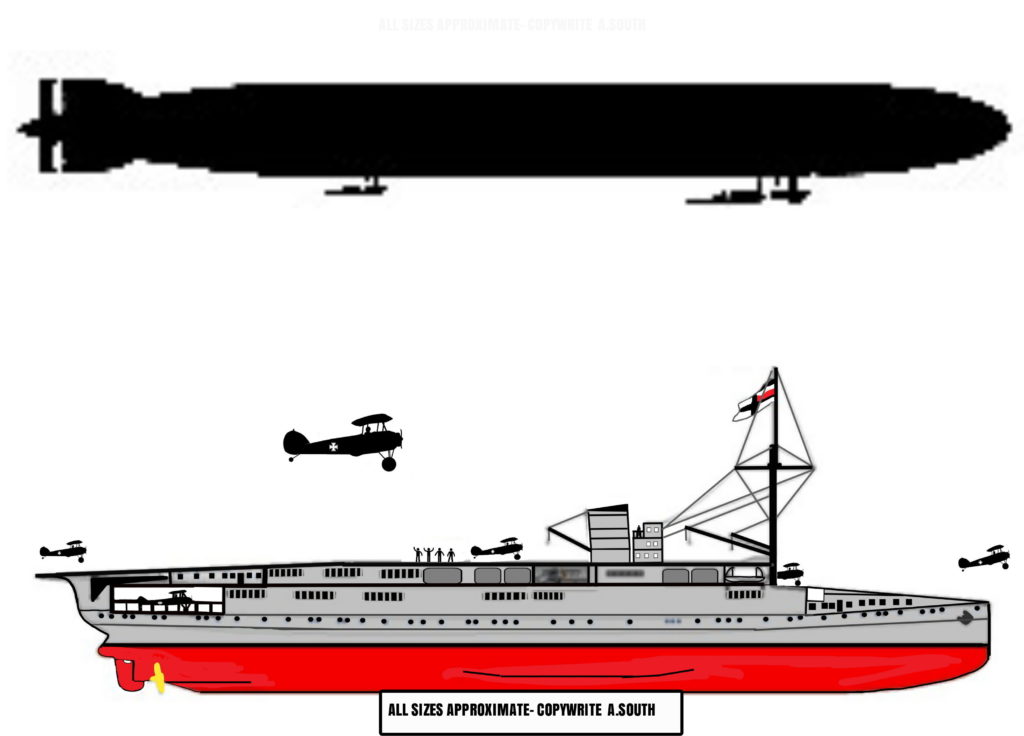

Finally, under the authority of the Air Department of the Reich’s Navy Office, plans were drawn up for a

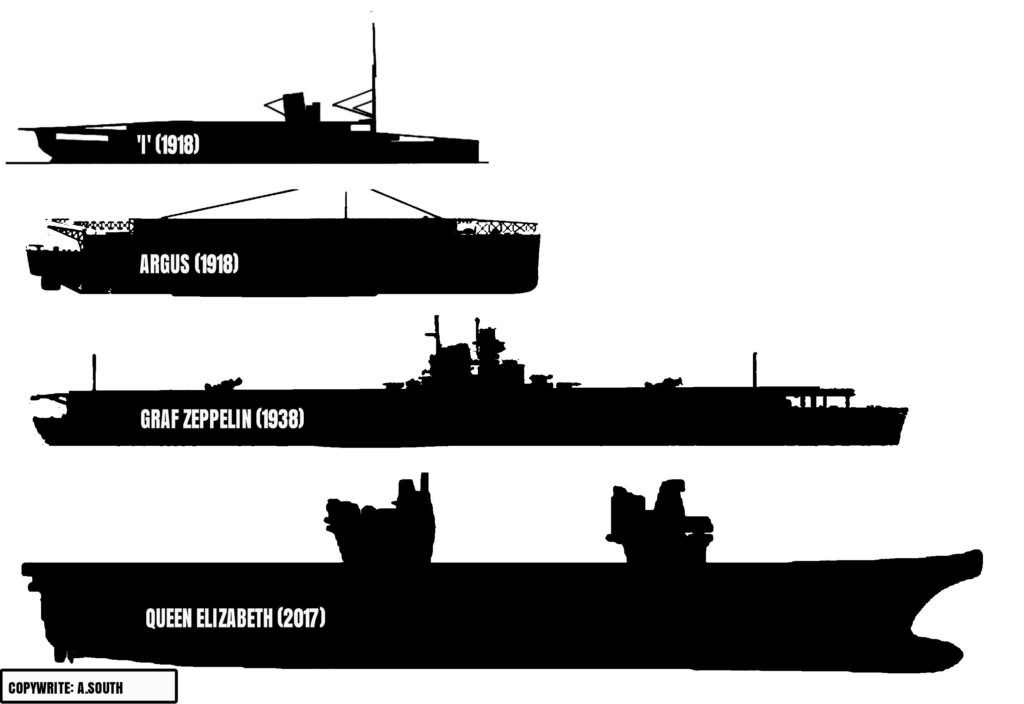

flight-deck-equipped aircraft carrier, such as the British were developing with the HMS Argus.

It is unclear if the Germans were aware of the Argus’s development, but surprisingly the two embryonic

carriers were to be similar, to a large degree in their layout. Both had open flight decks running the

length of their hulls, but it was the German designers that conceived the modern island layout. The

Argus had no superstructure to break the line of her main flight deck. To the question of who thought of

a decked carrier first, in 1912, the ship builder William Beardmore had offered the concept to the British

Admiralty for an aircraft carrier design with a continuous, full-length flight deck, but it was not accepted

until 1916 with the purchase of the Italian ocean liners Conte Rosso and the Giulio Cesare. It was on the

hull of the latter that the Argus was to be built.

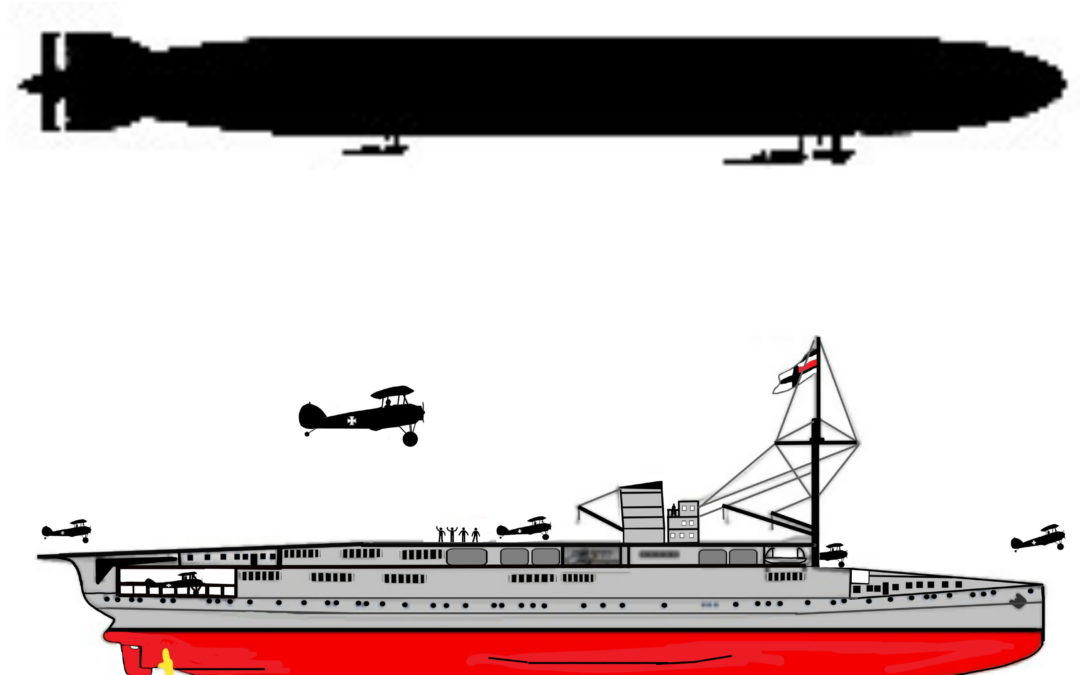

The German carrier or Flugzeugdampfer, (“aircraft steamer,” a design which was a combination of a

‘airplane ship’ and an aircraft carrier) was to have been 518 feet 4 inches in her overall length. The Argus

would exceed that length by an additional 46 feet 7 inches. The Flugzeugdampfer’s length between her

perpendiculars was 490 feet 9 inches, (46 feet 7 inches less than the Argus). The ships beam was

planned as 61 feet 8 inches, (6 feet 2 inches narrower than her British rival). She had a draft of 24 feet 4

inches, (1 foot 4 inches less than the Argus) and displaced 12,585 (with Argus heavier, at 14,450) metric tons. The ships power source was to be two sets of Blohm & Voss geared turbines providing 14,000 shp

driving a pair of screws (compared to the British four propellers), the diameter of which is not recorded.

The details of the boiler system and electrical power plant are also unknown now. She was to bunker

1,500 tons of coal and both German and British vessels could achieve a theoretical speed of 20 knots.

The ship’s design envisaged two hangar decks for wheeled aircraft, which were 269 feet in length. The

third hanger was a hangar deck designed for seaplanes and was the longer of the three at 419 feet. The

Argus in turn also had three. All three hangars on the German hull were to be 60 feet 8 inches in their

width. The flight deck would have been 421 feet 7 inches long, (549ft. Argus) and 61 feet 4 inches wide.

All three of the hangars and the flight deck were planned as being mounted above the main structural

deck. The design included a take off deck on the bow, which would have been 98 feet 5 inches long and

135 feet 5 inches wide.

Erich Gröner, (a naval historian) claims that the ship was designed to carry either thirteen fixed-wing or

nineteen folding wing seaplanes, and approximately ten wheeled aircraft. The Argus had a larger ’air

wing with between fifteen and eighteen, all seemingly wheeled, but with no arrester wire yet

developed. Rene Greger (author) gives the German air complement as between eight and ten fighter

aircraft and a combination of fifteen to twenty bombers and torpedo floatplanes. The wheeled aircraft

were to land on the stern deck and launch from the forward deck. The seaplanes were to be lowered

into the sea and lifted with cranes. Her Armament remains unknown to us.

Prior to the war, the 2,585-ton Italian turbine-powered steamer Ausonia had been under construction in

Hamburg’s Blohm & Voss shipyard (as hull no 236). With the war, work came to a halt, but she none the

less (to clear the slip way?) was launched on April 15th, 1915. The German navy decided to convert the

incomplete hull into their first aircraft carrier and allocated her the construction name of ‘I’. If she had

been completed, she would have been assigned a permanent name, but it was the more usual practice

with German ships once ordered, to be given an ersatz name. For example, the first German

dreadnought, SMS Nassau, was laid down as Ersatz Bayern, or Bayern replacement. However, the ‘l’ was

the first of her type and not a replacement, she was not given an ersatz name. Conversion plans were

drafted up by Lt.z.S. dR Jürgen Reimpell of 1. Seeflieger Abteilung, (Seaplane Department) and his final

design proposals being completed by 1918. But by that stage in the war, it was really just a pipe dream.

Following Jutland, the burden of the war at sea had become more focused on the U-boat service and the

construction of the boats Germany would need to defeat the British. The final constructions of the

Imperial Navy, (the ‘I’ amongst them), were never to reach completion with the Armistice, in November 1918. In 1920, the Italian shipping company that had originally ordered the Ausonia, canceled its order

partly due to the post-war inflation in Germany and the substantially increased price of the ship. She

was sold to ship breakers in 1922 and broken up for scrap. Germany’s first foray into the aircraft carrier

was brief and had never progressed beyond the draftsman’s board. But it would be rekindled in the

1930’s and then ultimately extinguished with the Graz Zeppelin.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

https://forum.worldofwarships.eu

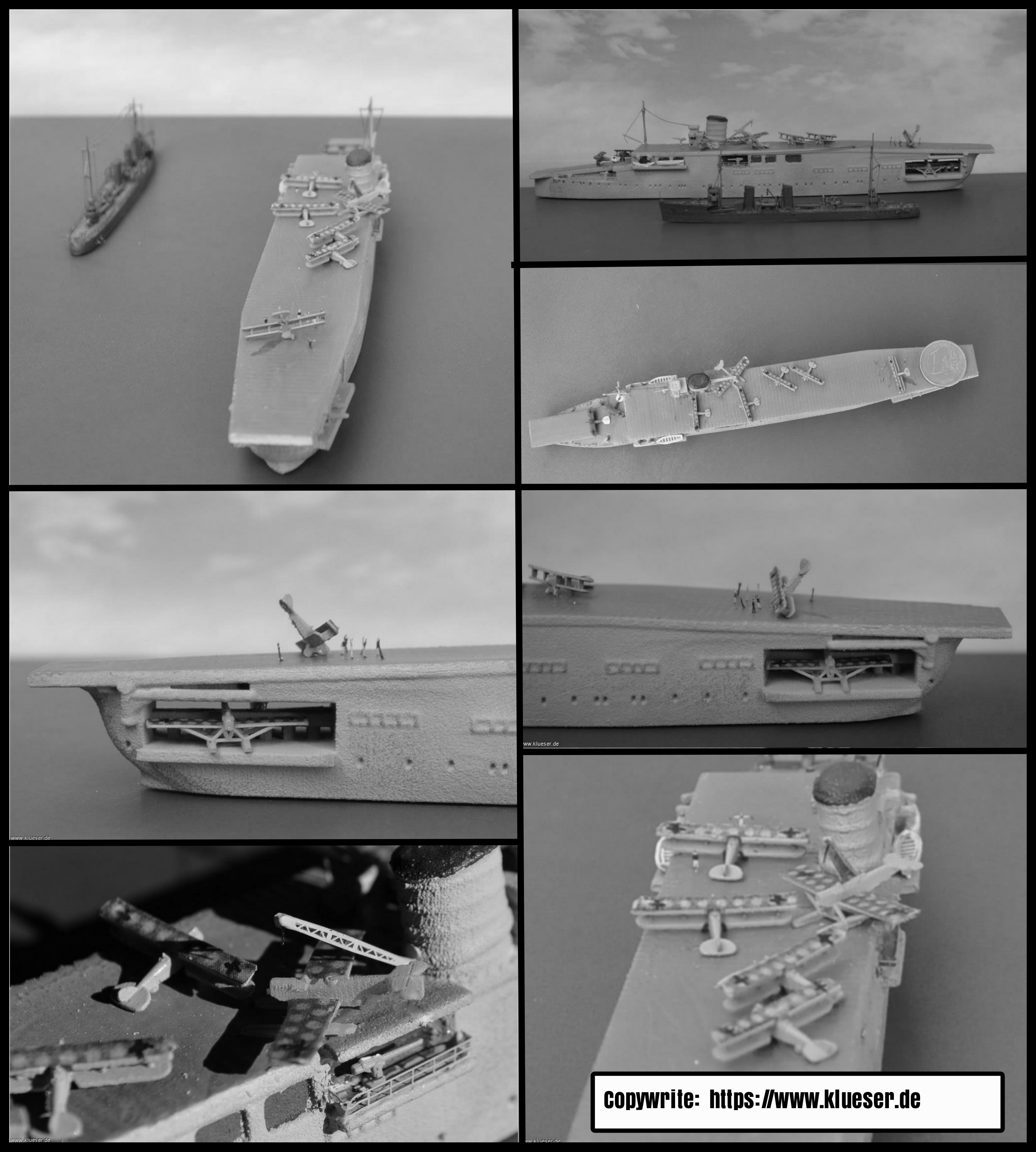

https://www.klueser.de

https://www.secretprojects.co.uk

https://en.m.wikipedia.org

Further Reading!

Follow Andy South’s fantastic Facebook Group!

Recent Comments