Special thanks to Andy South for sharing a snippet from his books detailing the career and design of HMAS Sydney. Andy has delved deep into the history of this ship and produced an entire series. If you enjoy the article, you will definitely love his book. You can purchase it on Amazon.

HMAS Sydney : Introduction

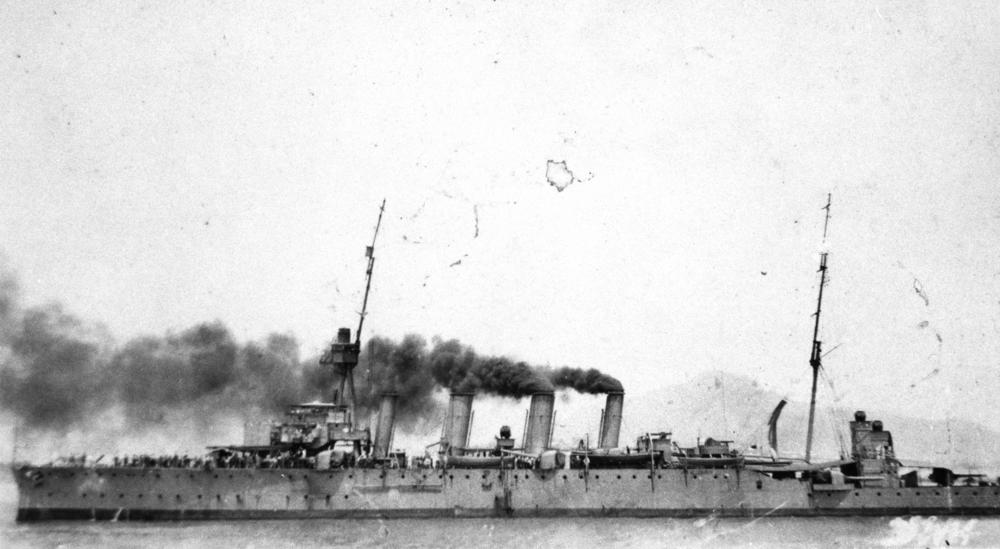

If you asked a group of naval or military historians to name one warship of World War One, (excluding capital ships), the odds are one of the most popular names given would be the German cruiser SMS Emden. Where that name is spoken, HMAS Sydney is closely linked, the two ships are forever intertwined in their places in history. No matter if you compiled the list in 1915, 1935, 1955 or today, the names Emden and Sydney would stand proud. An oddity when you consider a number of other Royal Navy cruisers achieved much more in ‘popular’ history.

It is not intended to demean her victory over the Emden and she had a full and active wartime service. Sydney claims the greatest number of war time miles sailed by a cruiser between 1914 and 1918. She saw active service in the Pacific, Indian ocean, Caribbean, South Atlantic, North Atlantic and the North Sea. But her fame, (or ‘super-stardom’) rests on one morning in November 1914. However HMS Kent saw more action during the early years of the war? She was present when Admiral Sturdee destroyed von Spee’s East Asiatic squadron. She forced the Dresden to scuttle herself in the Battle of Más a Tierra. Then she served on escort duty as well as in the Siberian Intervention during the Russian Civil War.

Then there is the Glasgow, a veteran of the battles of Coronel and the Falklands. Also the Cornwall, veteran of the Falklands, Rufiji Delta and the Dardanelles….. But none of these ships have the popularity of the Sydney, either during her time of service or since. The Sydney is unique in that she was the one that destroyed the famous Emden, a ship even more unique in that since August 1914 until the snowy day in 2019 that I sit here writing this, is admired, respected or maybe even loved by both sides.

Sydney was from her victory in the Indian Ocean, famous and a true superstar of her day. Her quarter deck was the one the important, the self-important, the public and the school boys wanted to be seen on. Her cap ribbon was the one the girls wanted. If she was a film star today she would be on the cover of Hello magazine almost every month and she would be the centerfold in other magazines. During the war in her home country she was idolized and deservedly for what she achieved was no mean feat. We will meet a certain gentleman in volume 2, (and I use the word loosely), that impersonated the role of having served on board the Sydney. Stolen Valor is the term in vogue today. But why Sydney, why not claim he survived a Jutland disaster, of how he swam away from the Queen Mary as she erupted? Why the Sydney who wasn’t even at Jutland? I can’t tell you why the Sydney was everyones darling, but I can tell you she was more than that one November morning.

She was present as the German Pacific Empire was lost, she hunted the Kronprinz Wilhelm. She fought Zeppelins, served in the Grand Fleet, saw the Kaisers fleet humbled in 1918. She was much, much more than just the Emden engagement, but to all but the tiny percentage of us, the rest of her service is forgotten, lost in the glow of her one great battle. These books will be my attempt to correct that. They present a chronological account of her service years, the excitement, the routine, the boredom, the repetition and the coaling.

These volumes are the result of three amazing web sources, which hold within their digital pages a dragons hoard of treasure.

The National Library of Australia has created a website entitled ‘Trove’ and within its pages are thousands of newspaper pages, that cover period from the 18th Century until the present time. From that site, I discovered many first person accounts that helped bring some colour and life to the account of the Sydney’s commission. But as the war develop and censorship grew, the accounts became less abundant. But in the year before the war, the site was priceless.

The Australian War Memorial holds thousands of images and files that relate to the subcontinent’s history. Within the memorial I found two journals written by members of the Sydney‘s crew:

The diary of Leading Signalman John William Seabrook recounts his time at sea serving on the HMAS Sydney between 1914 and 1918. (AWM ref:RCDIG0000351).

The journal entitled ‘Unknown Sailor’ is a hand-written diary (possibly that of a midshipman’s) and covers the period on-board from 25 July 1913 to 31 October 1916. (AWM ref:2017.7.110).

These two volumes provide the human side to the tale of the Sydney and are priceless in the information held within their 100 year old pages.

The other source is the naval-history.net. Within are the transcribed ships log of the Sydney from 1913 to 1914. The site is for any lover of naval history somewhere to visit and never want to leave.

Without these three sites these books would not be possible, or have such a depth of information about the life and times of the Sydney. At the end of each volume there is a full and detailed bibliography. Finally a thank you to the staff members at the AWM and National Library of Australia, who patiently answered my enquiries and were so helpful.

CHAPTER 1: CONCEPTION

From the latter part of the 18th Century, until 1859, the Australian continent depended on the ships of the Royal Navy, serving under a British Admiral, to provide for the colonies maritime defence. But in 1859, Australia was designated as a British Naval Station in its own right and until 1913, a squadron of the Royal Navy was stationed in Australian waters. The Australian Squadron was paid for, (and also controlled) by the Australian Commonwealth and (in time), crewed by Australian personnel.

In 1909 an Imperial Conference was held in the Empire’s capital, London, where it was decided to develop a naval force of at least one battle cruiser, three second class cruisers, six destroyers, three submarines and a number of auxiliaries, based in Australian waters. The decision on the 19th August 1909 between the British Admiralty and the Australian Government concluded an agenda to proceed with the establishment of an Australian Fleet Unit. The first units of this fledgling Navy, the destroyers, HMAS’s Yarra and Parramatta, reached Australian waters in November 1910and on the 10th July 1911, King George V bestowed the title of ‘Royal Australian Navy’ to the Commonwealth Naval Force.

A third destroyer, HMAS Warrego was commissioned at Sydney in June 1912 and in 1913 the battlecruiser, HMAS Australia and the light cruisers, HMAS Melbourne and Sydney arrived in Australian waters, concluding on the 4th October 1913, with the new Australian Fleet entering Sydney harbour for the first time. In October of the same year the formal control of these vessels was passed to the Commonwealth Naval Board, bringing direct Imperial control to a conclusion.

Of all the Royal Australian Navy’s first generation warships, the most famous was the Town class light cruiser, Sydney. The class comprised of twenty-one ships built for both the Royal Navy (RN ) and Royal Australian Navy (R.A.N), between 1903 and 1916. The vessels had been conceived and designed to serve as long-range cruisers, with the task of patrolling those vast expanses of the globe that in the early 20th Century coloured the Imperial red of the British Empire. They were to show the flag in peacetime and in the time of war, safeguard the Empire’s supply lines, the trade routes and the maritime links that bound the worlds biggest empire together. They were on their conception rated as second class cruisers and were to be built to six varying designs:

- Bristol sub-class (five ships)

- Weymouth sub-class (four ships)

- Chatham sub-class (three ships)

- Sydney sub-class (three Chatham design, R.A.N ships)

- Birmingham sub-class (three ships, plus one similar R.A.N ship)

- Birkenhead sub-class (two ships).

The 21 ships that comprised the class were all to bear the names of Australian or British cities or towns.

The major difference between the other five sub-classes and the Chathams was their revised armour scheme. Whilst the earlier ships were designed to be protected cruisers, relying on an armoured deck deep within the ships hull, that was there to protect both the machinery and magazines, the Chathams were to rely on a vertical belt of armour.

CHAPTER 2: THE SHIP

DIMENSIONS

The R.A.N’s three new four funneled cruisers, HMAS Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney, had a standard displacement of 5,400 long tons (5,500 metric tonne) and 6,000 long tons (6,100 t) when they were fully loaded. The cruiser’s hulls were 456 feet 9¾ inches (139.2 m) overall in length and 430 feet (130 m) between the perpendiculars,(a football or ‘soccer’ pitch is 306 feet in length). They had a beam of 49 feet 10 inches (15.19 m)and drew 19 feet 8 inches (5.99 m) in the draft. (Janes fighting ship 1919 records her dimensions as 15¾ inches (mean) 17¾-18½ inches (max)).

MACHINERY

The ship’s twelve water-tube boilers were located within three separate boiler rooms, (which lay beneath the armoured deck), where the coal and oil fuelled Yarrow boilers provided steam for the Parsons geared turbines. The turbines each sat in their own compartments laid across the width of the hull. These in turn drove four shafts and attached were four manganese bronze propellers. The turbines provided an output of 25,000 horsepower (19,000 kW) at 500 rpm. The main condensers and auxiliary machinery were in turn housed in two compartments directly aft of the main engine rooms, The steam and manoeuvring gear for the turbines was arranged against the forward bulkhead in the centre engine-room. The ships lacked cruising turbines, but were instead equipped with a special series of blades for cruising purposes, which were fitted in each of the high-pressure turbines. The boiler rooms were adapted for use with the closed stoke hold system of forced draught, the supply of air being provided by steam-driven fans. Oil pumps were provided for both oil fuel and forced lubrication purposes. Her condensers in 1919 are listed as ‘Uniflex’.

The Chatham class ship’s used a mixture of coal and oil for fuel, with their bunkers holding a capacity of 1,353 tons of coal and the tanks 260 tons of oil. (Janes 1919 lists her coal capacity at 750 tons ‘normal’, 1240 and “about” 260 tons of oil maximum). They had been designed to achieve a maximum speed of 25 knots (28.7mph/46.3 kph), but the Sydney was to exceed that with a mean maximum of 25.7 knots (29.5 mph/47.5kph) during her trials in 1913. (Janes 1919 describes her trials as 30 at 3/4’s power (22,400shp) and 8 hours at full power(25,800 shp) as achieving 25.7 knots)). Her economical cruising speed was in 1921, 11 knots (12.6 mph/20.3kph) and in 1926 11.5 knots. The Chatham’s range of steaming was 4,460 nautical miles (8,260 km) at 10 knots. At that speed she burnt 3.29 tons of coal per mile. Coal is given as selling for 2 shillings 6 pence per ton in 1912 in an Australian newspaper, (but the admiralty would purchase in bulk, not from a newspaper, but these are figures of curiosity, not to be taken as serious or gospel), which means her full 1353 tons would cost £169 to £170 (2018=£13,211) and she averaged between 9 to 10 pence per mile (2018=£3.26).

CREW

The Chatham’s standard crew numbers in times of peace is listed as 376, but with the demands of the service, that figure would fluctuate. In the war her crew are given as numbering a maximum of 475, comprised of 31 officers and 454 sailors. In her 1913 log book, her compliment, (on commissioning), is numbered as 392, (of which 47% were of Australian birth), comprising of 20 Officers, 145 Seamen, 177 Engine room establishment and 50 other non-executive ratings.

ARMAMENT

The cruiser’s main armament was comprised of eight single BL (breech loading) 6-inch Mark XI guns. The foremost gun (or bow chaser) sat to the rear of the fore-deck, with two further weapons located parallel with the bridge. Guns number 4 and 5 sat to the rear of the ships third funnel and guns 6 and 7 were parallel with the rear mast. The final 6-inch was to the rear of the deck (a stern chaser). Their broadside was comprised of six of the 6-inch weapons, capable of firing to either port and starboard, depending on their location. But firing over the bow or stern she could in theory use three of her guns, but the two guns located under the bridge wings and behind the aft rear mast, had restricted fire, being unable to range fully directly over the bow or stern, due to superstructure obstructions

The weapon had first seen service on board the armoured cruiser HMS Black Prince in 1906and was to go on to be used as secondary guns on many of the Royal Navy’s pre-dreadnoughts. They were however to prove in service, to be too heavy for the gun crews to aim manually, especially on the smaller cruisers. In the latter years of World War one, hydraulic power gear was to be installed to some of the weapons installations. The weapon was both shorter than its predecessors and lighter, with a small loss of range of 600 yards (548.64 m). But the model proved to be accurate, far easier to work, (especially in rough weather) and with a faster loading time.

The barrel construction was of a tapered inner ‘A’ tube, with a wire full length jacket, breech ring and a breech bush screwing into the ‘A’ tube. The gun’s weight was 19,237 lbs. (8.7 tons) 8,726 kg)), with a length of 25 feet, 9 inches (7.867 m) overall and it’s bore length was 25 feet (7.620 m). A modern ‘compact’ car weighs on average 1.32 tons, resulting in each barrel equated to 6.59 ‘compact’ cars! The weapon could achieve, with a competent gun crew, a rate of fire of between 5 to 7 rounds per minute. One source notes the rate of fire for the weapon as 12 rounds per minute under a Gunlayer’s Test. A process where individual gun-layers fired over a short distance at small target and being allowed a number depending on the calibre of their weapon. The weapon was also capable of 4 rounds per minute within Battle Practice, but it doesn’t clarify for what type of vessel these figures applied to. The weapon could use a common pointed capped (CPC) and semi-armour piercing (SAP), filled with TNT.

The bursting charge was for a CPC 4crh, 7.5 lbs (3.4 kg), with a shell length of 23.5 inches (59.7cm). For the HE 4crh, the bursting charge was 13.3 lbs. (6.0 kg) with shell lengths of 22.9 inches (58.2cm). The propellant charges were 32.1 lbs, (14.6 kg) and 33.1 lbs, (15 kg), producing a muzzle velocity of 2,937 feet per second (895 mps), or 2.63 Mach. The barrel life has unfortunately not been recorded within today’s records. The Sydney had a larger magazine capacity which allowed for 200 rounds, compared to 150 in the earlier sub-classes.

The weapon, firing a 100 lbs (45.36kg) H.E shell, at an elevation of 13 degrees could range out to 11,200 yards (6.36miles/10,240 m), increasing at 15 degrees to 14,310 yards (7.43 miles/13,085 m). It’s maximum range is recorded as 18,000 yards (10.22 miles/16,000m), with a 22.5° degrees elevation, but that’s at a rate of degrees beyond the Sydney’s mounting.

Over 3,000 yards (2,740 m) firing at Krupp cemented armour plate the weapon could penetrate 3.0 inches (7.6 cm) of armour with a 2crh 100 lbs, (45.4 kg) CPC shell. Firing a 4crh 100 lbs (45.4 kg) CPC shell this increased to 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) at the same 3,000 yards (2,740 m) distance.

We have no weight recorded, with or without the shield for the weapons mountings. But the elevation rate ranged between -7 and +13 degrees, increasing under modifications to +20 degrees on some later units. The weapon was only able to be elevated and trained manually and it could train to between +150 / -150 degrees (approximately). The guns recoil is also unfortunately not recorded. As we progress through the ship’s career we will at the relevant time make a Sydney v Emden main calibre performance comparison.

The weapons had gun shields fitted for the gun crews protection, but the weapons were dispersed separately around the hull, to avoid the peril of one shell strike rendering more than one gun out of operation .

Sydney’s anti-aircraft armament consisted of a single 3 inch (76 mm) quick-firing high-angle anti-aircraft gun. But it is important to note that at the wars outbreak the winged ariel threat was all but nonexistent. What anti-aircraft weaponry she had during the war is better defined as anti-airship or Zeppelin. The lone QF (quick firing) 3-inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft gun she carried was to become the British standard anti-aircraft gun for use in the defence of the United Kingdom against German Zeppelin’s and bombers, as well as also on the Western Front. It was to be a common weapon onboard British warships in the war and would go onto serve in the next war within the submarine force.

The 20 cwt referred to the weight of both barrel and breech, in order to mark it from the other 3-inch guns ( 1 hundredweight equates to 112 lb), hence the barrel and breech together weighed 2250 lb). Whilst the other AA guns had a bore of 3-inches, the term “3-inch” was only ever used to identify this gun between 1914-1918 and commonly referred to as a “3-inch AA gun”. The weapon was based on a pre-war Vickers naval 3-inch (76 mm) QF gun, but was designed with a number of modifications that had been sought by the War Office in 1914.

One of these modifications was the introduction of a vertical sliding breech-block to allow for a semi-automatic operation. When the gun was recoiled and run forward after firing, the motion served to open the breech, eject the empty cartridge case in the process and was then retained in the open position, ready to be reload, with the striker cocked. When the gunner loaded the next round, the block closed and the gun was fired.

The original or early 12.5 lb (5.7 kg) shrapnel shell had a velocity of 2,500 feet per second (760 m per sec), but it was found in service to cause excessive barrel wear and prone to being unstable whilst in flight. In 1916 a 16 lb (7.3 kg) shell, fired at the lesser 2,000 feet per second (610 m per sec) proved to be both ballistically superior and more suited to a high explosive filling.

The gun and breech weighed 2,240 lb (1 ton)1,020 kg)) and had a barrel bore length of 11 ft 4 in (3.45 m), (45 cal) and was 11 ft 9 inches (3.58 m) overall. The gun’s crew was comprised of 11 men and they served it with a 12.5 lb (5.7 kg) shell in 1914, increasing two years later to the 16 lb (7.3 kg) shell. The weapons calibre was 3-inch’s (76.2 mm) and could, (subject to ship structure obstruction), traverse over 360 degrees, with a rate of fire of between 16 and 18 rounds per minute. Its effective firing range was 16,000 ft (4,900 m) and the maximum firing range was 23,500 ft (7,200 m) with a 12.5 lb shell and 22,000 ft (6,700 m) with a 16 lb shell. On average a Zeppelin had an operating altitude of 16,500 feet (5,000 m) and a ceiling of 21,000 feet (6,400 m), both within the range of Sydney‘s lone A/A gun.

Aside from a selection of small arms, the cruiser also carried ten 0.303-inch machine guns (eight Lewis guns and two Maxim guns), for use by her landing parties.

Sydney was fitted with two 21-inch torpedo tubes, with seven torpedoes Mark XI carried. She was also later in the war equipped with two hydraulic-release depth charge chutes for anti-submarine warfare use. The ship was supplied with a single 12 pdr 8cwireless field gun and four 3 pdr Hotchkiss saluting guns to complete her armament.

The ship was fitted with electric hoists to feed her guns.

DIRECTORS

Two years into the war, it was decided to retrofit the class with gunnery directors, but only as time, resources and the opportunity would permit. Sydney was to receive her directors during her 1917 Chatham refit. The class was in general, (Brisbane excepted owing to her ongoing service in the Pacific), to be supplied with their directors between 1917 and 1918. The Chatham’s were not to be supplied with a Dreyer Table or any form of fire control tables during the war period.

ARMOUR

The fundamental difference between the Chathams and the earlier Town class ships was their revised armour system. The earlier ships had been classified as protected cruisers, with a thicker armoured deck within the ships hull in order to protect their machinery and the magazines. The Chatham’s were instead constructed with a vertical belt of armour. This belt was comprised of 2 inches (51 mm) of Hadfield nickel-steel, laid over 1 inch (25 mm) of high-tensile steel, which tapered from 3 inches down to 2.5 inches (76 to 64 mm) forward and to 2 inches (51 mm) aft. The belt sat between 8.25 to 10.5 feet (2.51 to 3.20 m) above the waterline, submerging to 2.5 feet (0.76 m) beneath it. It formed part of the load bearing structure within the ship, reducing the overall weight of structure required. A thin armoured deck of 3⁄8 inch (9.5 mm) ran over most of the length, but lessened to 1.5 inches (38 mm) over the ships steering gear and served mainly as a watertight deck. The Sydney’s forecastle was extended aft, reaching two-thirds along the length of the ship and permitting two additional guns to be raised up onto the forecastle. As a result the ships’ metacentric height was reduced, making for better gun platforms. In addition Sydney was built with a 4 inch armoured conning tower and as a final note, the Officer’s accommodation was moved back to the rear of the ships in Sydney’s class. As additional protection below the waterline the hull subdivided into numerous watertight compartments. Additional protection was afforded by watertight coal bunkers, extending along each side of the ship. The ships double bottom extended under the machinery spaces and the forward and aft magazines were sub-divided into numerous compartments.

Her double bottom extended beneath the magazine and machinery spaces.

BINOCULARS, WIRELESS & ELECTRICS.

During September 1914, the Chatham class were issued with five additional pairs of Pattern 343 Service Binoculars. The Sidney was built with two masts, both which were fitted with yards, ‘for wireless telegraphy and signalling, the foremost mast also carrying a searchlight, one of four on the ship. The ship was electrically lit throughout and was fitted with electrically-driven coaling winches, ammunition hoists, fresh and salt water pumps and ventilating fans. She had a complete system of voice pipes, telegraphs and telephones, as well as a “submarine sound signalling apparatus” [*].The magazine and shell rooms were lighted and ventilated with the latest system and were kept at a low, even temperature by a special refrigerating plant provided for the purpose.

SHIPS BOATS.

The Sydney’s ships boats compliment on commissioning was comprised of:

- 3x cutters, (1 x 34 feet, 2 x 30 feet in length)

- 3x whalers, (27 feet)

- 2x drop-keel gigs, (30 feet)

- 2x skiffs, (16 feet)

- 1x steam cutter, (35 feet)

- 1x balsa raft, (13½ feet).

The Chatham’s were ordered in July 1914 to land one of their two 30-foot drop-keel gigs.

MOTTO, BATTLE ORDERS, BELLS, PENNANTS AND COST.

HMAS Sydney’s motto was “Thorough and Ready” and she was to emerge from the first world war with just one battle honour, “Emden 1914”. However following a review of the R.A.N honours system in 2010, Sydney was to be retroactively awarded two further honours: “Rabaul 1914” and “North Sea 1917 to 18”.

HMAS Sydney carried two ships bells, the first of which was to commemorate the ship’s commissioning in 1913 and the second was presented to the ship on her first entrance into her namesake port in later in the same year. The second bell was made of solid silver and weighed 62.5 Ibs approximately. It bore a representation of the City of Sydney’s Coat-of-Arms accompanied by the inscription ‘Presented by the citizens of Sydney to HMAS Sydney‘. Both the coat-of-arms and the lettering were hand carved. When HMAS Sydney (II) arrived in Australia following her commissioning, the bell was presented to her in a continuation of the tradition. Sadly the bell was to be lost when HMAS Sydney (II) was sunk on the 19th November 1941, following her battle with the German commerce raider Kormoran.

The Sydney’s pendant Numbers were ‘A1′ (1.18), ’52’ (4.18)and her cost of construction was approximately £385,000 or £41,965,000 in today’s prices.

Notes

The next section will detail the crew of HMAS Sydney, stay tuned!

If you want to read the book, be sure to check it out on Amazon: THE SYDNEY: The birth of Australia’s fleet (1913) ( vol 1)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the author at andyuknaval@gmail.com.

Recent Comments