One of the most poignant human stories to come out of the Battle of Jutland was that of sixteen year old John Travers Cornwell, J/42563. He was a Boy, 1st Class, aboard HMS Chester during that clash of fleets at the end of May 1916, and he became one of the youngest recipients of a Victoria Cross.[1] Tragically, the award was posthumous and – as so often with that decoration – wrapped in politics that speak as much for the ideals of the day as they do for Cornwell’s actions.

Cornwell was 16. He had joined Chester just five weeks earlier, on Easter Monday 1916. His youth on joining up seems remarkable today, but at the time was not unusual. Boys often left school at relatively young age and found jobs. At the time there were two ways for boys to enter the Royal Navy. The first was as a cadet officer – a midshipman. This involved training via Admiral Sir John Fisher’s education scheme, which was designed to produce officers with technical competence in modern warfare. This system was as revolutionary as the naval hardware with which Fisher is usually associated, but has been often forgotten to history. Boys wanting to join at this level typically began studying at what were known as ‘cram’ schools around age 10, joining up at age 13-14. It wasn’t cheap: fees in 1905 were set at £75 per annum, in part to keep the poor out.

(Royal Collection Trust)

The poor, however, could simply enlist as ordinary bluejackets once they turned 15. The official rank while training was ‘boy’, which some recruits retained when sent to their first ship. This training, too, focused on education, this time geared to the lower deck and including reading and writing. Reasons for joining varied. In this age of social militarism and Imperial patriotism there was social status to be gained from serving, but a major factor was that the navy provided housing, education and pay. What this meant was that a fair proportion of the regular bluejackets at Jutland were of similar age to Cornwell, often not much older.[2] And some of the midshipmen and junior officers were also of similar age.

Their numbers were surprising. A statistical analysis covering 380,000 RN personnel records was completed in 1915 and suggested that up to a third of those who joined up in 1914 – when a call went out for volunteers – were under 18.[3] This was startling by modern standards but not unusual at sea in any of the developed nations through the twentieth century wars: for comparison, at the end of the Second World War some 20.72 percent of the sailors serving in the US Navy were under 20.[4] Still, up until early 1918 the British army would not allow anybody under 19 to serve at the front, although some recruits lied about their age.

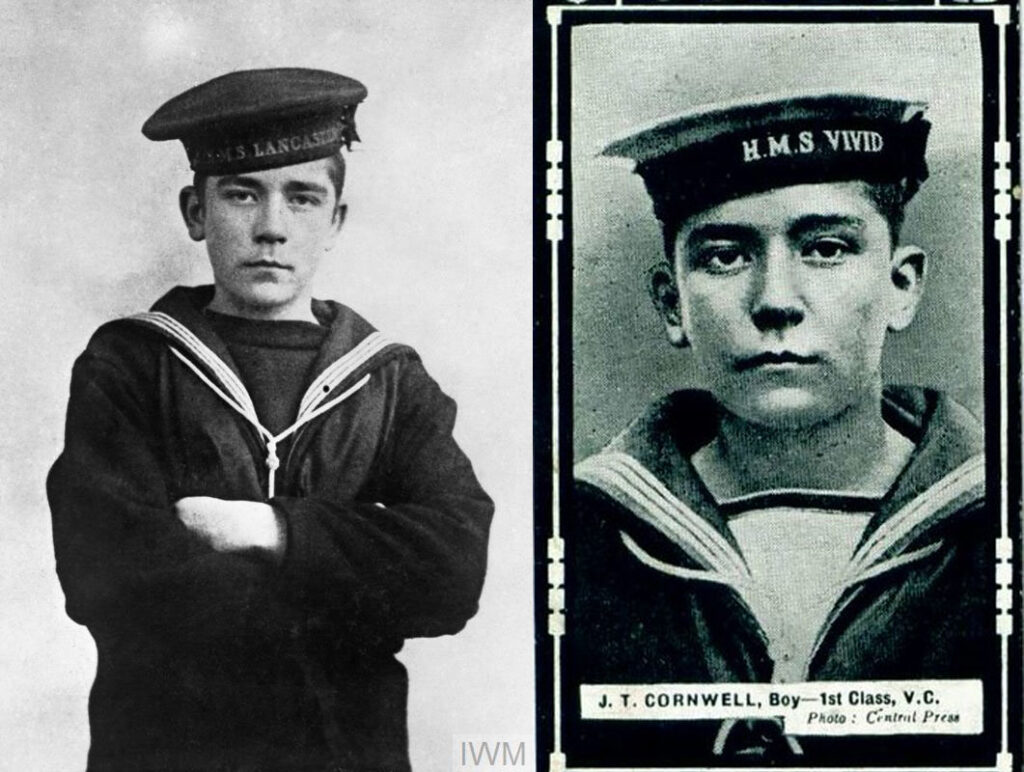

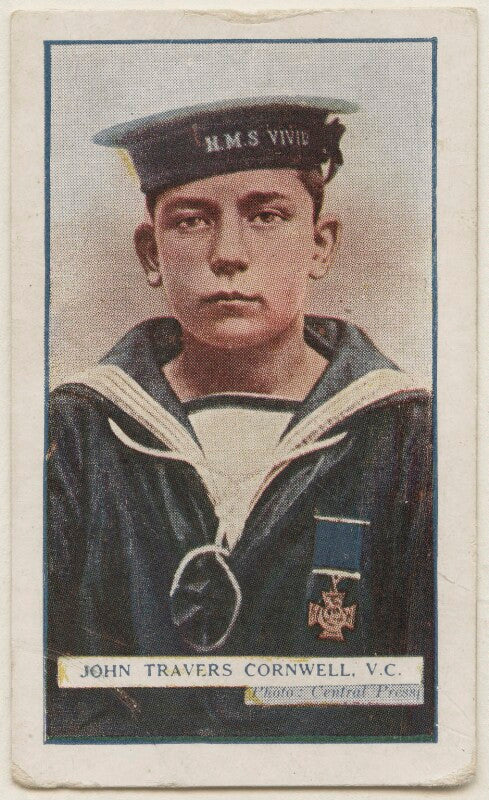

Cornwell, in short, was not unusual. Indeed, his story seems to have been much like that of many working-class recruits. He was born on 8 January 1900 in Leyton, to Eli Cornwell (1854-1916) and Alice Lily Cornwell, nee King (1871-1919). His given name was John, but he became Jack in the usual fashion of the day. Eli Cornwell was a former soldier and now train driver. Lily was Eli’s second wife, meaning that Jack had a half-brother, Arthur (b 1888) and a half-sister Alice (b 1890). Again, this was not uncommon: at the time women died with dismaying frequency, often after childbirth, and men were often left as widowers with a young family. Eli Cornwell’s second family grew rapidly and Jack was eventually one of four children. One younger brother was George, and it was apparently George’s photo that was issued as a picture of Jack after his death, complete with the name of HMS Lancaster on the tally (hat band), a ship on which Jack Cornwell never served.

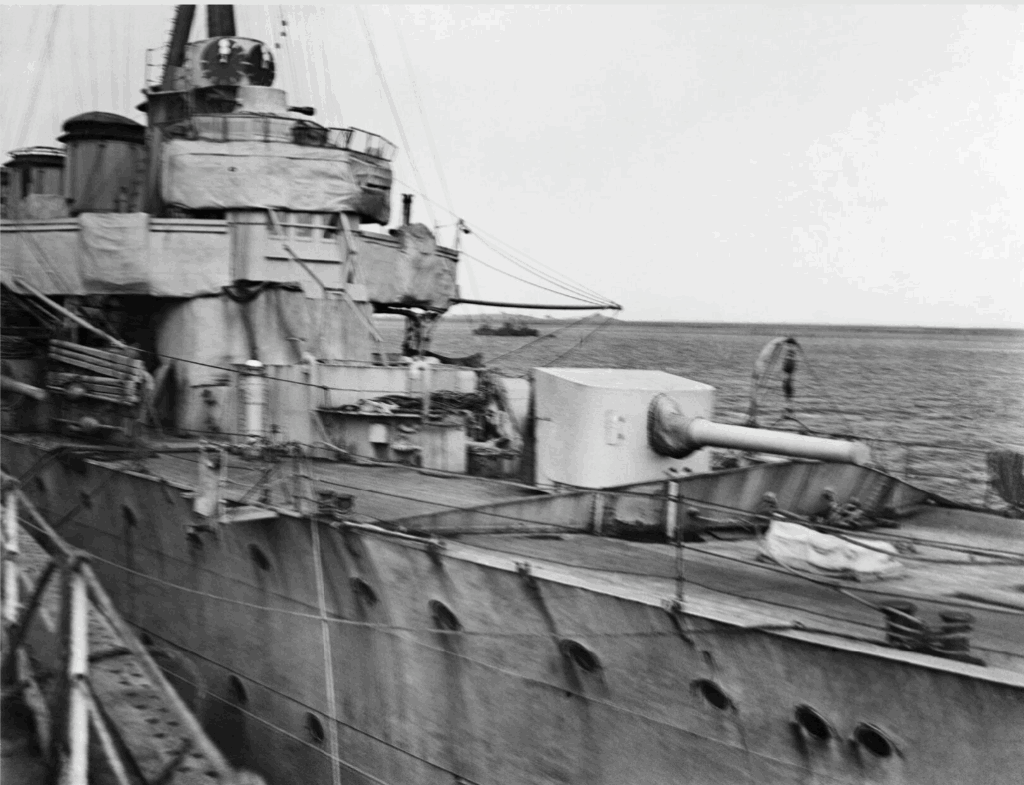

The family moved to Little Ilford, and Jack went to Walton Road School. In 1913 he left school to become a delivery boy for the tea company Brooke Bond.[5] His parents did not want him to join the navy when war broke out, but when he turned 15 he enlisted and was sent to the Keyham Naval Barracks at Devonport.[6] In April 1916 he graduated as a Boy, 1st Class, and on Easter Monday joined HMS Chester as sight-setter for the forward 5.5-inch gun. In battle he wore a Graham Pattern 555 Telaupad – the proprietary name for a set of wired headphones – down which the fire control team issued elevation and training angle data, which Cornwell applied to the weapon.[7] During battle he and the rest of the gun crew were protected only by a shield that did not extend down to deck level. This cruiser was attached to the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron, under Rear-Admiral Sir Horace Hood, which in May 1916 was temporarily stationed in Scapa Flow, with the Grand Fleet.

The battle of Jutland began with a clash of battlecruiser forces mid-afternoon on 31 May. The Grand Fleet was some way to the north, and Admiral Sir John Jellicoe sent Hood’s squadron south at speed to support Vice-Admiral Beatty’s battlecruisers. Around 5.27 pm,[8] Chester’s lookouts spotted gun-flashes and Captain R.N. Lawson turned southwest to investigate them. It was a classic North Sea day with intermittent mists and patchy visibility, with the result that the ship ran into the 2nd Scouting Group of Konteradmiral (Rear-Admiral) Frederich Boedicker. During the clash that followed Chester came under fire at short range from four German light cruisers, suffering at least 17 5.9-inch hits in just five minutes, doing substantial damage to her upperworks and knocking out four guns. Her gun crews were badly hit, in part because the gun shields did not extend to deck level. A significant number of the 31 dead and more than 40 wounded suffered lost limbs as a result.

Cornwell was among the first hit, suffering a chest wound, but stayed at his post as the gun crew fell around him. Eight of the ten were killed outright. During the next few minutes, as the ship turned away and Hood’s battlecruisers opened fire on the German cruisers, Cornwell was seen quietly standing at his post, with the dead and wounded around him. He was still there when the first aid parties arrived a quarter-hour or so later. Chester was too badly damaged to continue the fight and was detached to return to Britain. The wounded were taken off by tender on 1 June. At the Grimsby and District Hospital, Dr C. S. Stephenson did what he could for Cornwell, but in these pre-antibiotic days the prognosis was grim. Stephenson had the difficult job of telling this young man the bad news. Cornwell died on 2 June. His mother was not able to get there in time.

Cornwell’s family had little money: his body was taken to London where he was buried at the Manor Park cemetery in a common grave, No. 323, a pit into which multiple coffins were interred. Lawson wrote to Cornwell’s mother, describing how her son had quietly remained at his post ‘with just his brave heart and God’s help to support him… I cannot express to you my admiration of the son you have lost to this world. No other comfort would I attempt to give to the mother of so brave a lad, but to assure her of what he was and what he did, and what an example he gave.’[9] He hoped to have a plate made with Cornwell’s name and the words ‘Faithful unto death’, for the boys’ mess, and made clear he would ‘bring his name prominently before my Admiral.’[10]

Such a letter was typical of the time. When the First World War broke out the western world, and particularly the British Empire and Europe, was amidst its ‘social militarist’ era. This social movement had gained pace particularly after the Crimean War and was widely held by the turn of the twentieth century. It was a complex phenomenon, but the aspect we are interested in here was the way this phenomenon attached emotional value to heroic deeds in the battlefield as a way of obtaining social status. In this mind-set, specific actions carried symbolism and emotional weight among the public, irrespective of whether they were so or not. At sea, a commander who turned his ship towards the enemy was judged brave and heroic. One who turned away – irrespective of the tactical sense of it – was judged cowardly and weak. Standing up to enemy fire without flinching was considered to show strength of character. So too was doing duty irrespective of the circumstance. It was this last that gave Cornwell’s actions such power in the popular mind.

This mind-set also framed the nature of the letters that commanding officers were expected to write to grieving family. Of course the ideals of the day were not held by all. ‘War poets’ such as Vidal Sassoon seized upon such post-fact praise as facile and empty, to the chagrin of some officers who argued that the sentiment was genuine. Indeed, one time in 1917 Sassoon found himself target of brisk criticism during an evening dinner with a decorated brigadier and former commander of the Royal Navy’s Hood Battallion, Bernard Freyberg.[11] However, there is good reason to suppose Lawson’s remarks were genuine. He knew Cornwell was a boy, fresh to the ship, yet he not flinched or crawled away to hide. That struck chords both with navy tradition and the concept of period bravery.

Jack Cornwell’s story might have ended there, but Jutland had not been the ‘second Trafalgar’ the public expected, and then the Admiralty mishandled the public-relations, provoking controversy. Cornwell’s story and the fact of his being buried in a pauper’s grave hit the media in early July, spurring a public outburst of emotion, and for the Admiralty his tale suddenly became one way of recovering face with the public. A second funeral was organised with parade and full naval honours, and Cornwell’s body was dug up for the purpose.[12] The event was organised for 29 July. Hundreds of well-wishers lined the route, including boy scouts. Cornwell had a new coffin bearing a plaque with the words ‘Faithful Unto Death’.[13] Those in the parade included boys from HMS Chester, Admiralty representatives, clergy and local dignitaries. It was filled with pomp and ceremony, and Cornwell was finally laid to rest, for a second time, in a grave of his own.[14]

The possibility of further recognition was raised in the House of Lords on 26 July by Lord Charles Beresford – the same Beresford whose feud with Fisher had ripped the navy in two a decade earlier. He now asked whether the navy proposed to give Cornwell a VC. While ‘there must have been hundreds of similar cases to that of the boy Cornwell’, Beresford declared, the honour would ‘be an example to the boys of the Empire at their most susceptible age’.[15] The Duke of Devonshire, Victor Cavendish, demurred: no report had yet been received from Jellicoe and until it was, government would not consider individual cases.

As it happened, Cornwell’s action had already been officially recognised by Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty, who was impressed by this ‘splendid instance of devotion to duty’, recommending ‘special recognition in justice to his memory.’[16] It took time for the wheels to turn, but in September Cornwell was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, which his mother received personally from the monarch, George V.[17]

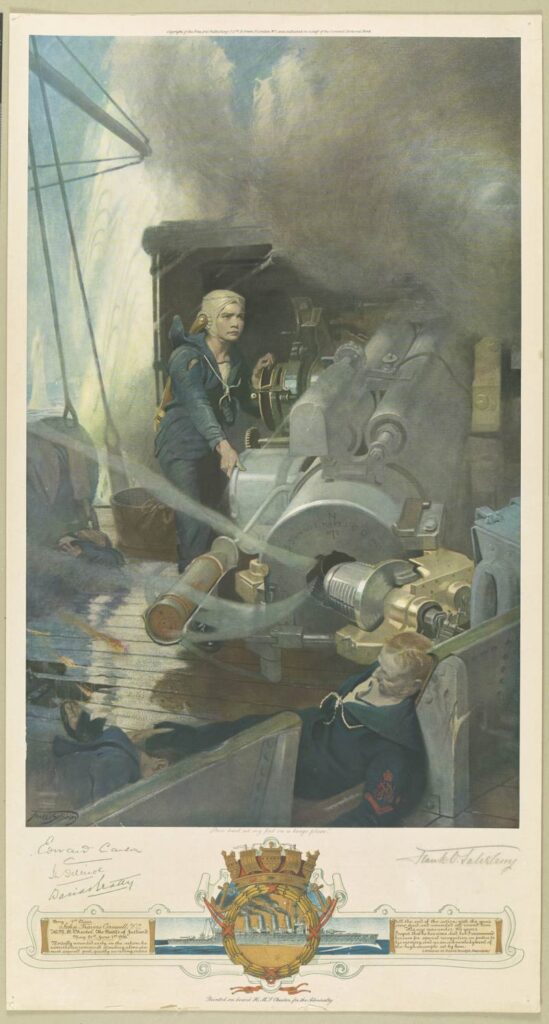

History has remembered Cornwell on multiple levels. One involves misinformation that circulated at the time. Media demanded a photo of him. One had been taken while he was training, but the family apparently did not have it. Instead a picture was hastily provided of George Cornwell, one of Jack’s brothers, with the tally for HMS Lancaster on his hat. There was a strong family resemblance and this became the definitive picture. Oddly, the genuine original of Jack while training at HMS Vivid was used as the basis for a cigarette card. Later, when a formal portrait was produced by Frank O. Salisbury, his younger brother Ernest stood in as the model. The artwork, titled ‘Thou hast set my feet in a large place’, was presented to the Admiralty on 23 March 1917.

Jack Cornwell’s death was not the only loss his mother had to bear. On 25 October, just a month or so after Jack’s second interrment, Eli Cornwell died at age 64. He was then serving with the 57th Protection Company of the Royal Defence Corps,[18] and was buried with his son. Jack’s brother Alfred was also killed during the First World War. It had been a tragic time for the Cornwell family.

From the perspective of history one question seems clear. Why Cornwell? Beresford was right: there were many other deeds of similar nature during the dramatic afternoon and evening of 31 May 1916. Many went unheralded, even unseen. So why this one boy? It is a question that can be asked of any decoration for heroism. For every decoration awarded there were many actions of similar nature that went unrecognised. Ultimately the selection was political.[19] The general issue was well known and Cornwell’s VC no exception. His story was the right one at the time, a heart-felt moment that struck all the right chords with the public vision of warfare, gaining attention just when the nation was looking for a hero.

Much of the acclaim drew from a public need to find something positive in a battle that had not delivered a second Trafalgar – where, instead, Britain mourned more than 6,000 dead. The human loss of Jutland was easily on scale with any ‘push’ on the Western Front, and Cornwell proxied the loss felt by so many mothers across the grieving nation. His deeds fitted the social ideal of warfare perfectly. He was mythologised, his own reality lost to the point where even the face associated with the deed was not his. Nobody cared. The fact that Cornwell was dug up for the purpose of a parade and then reburied underscores the point. This, perhaps more than anything else, made clear that the sudden attention was not about Cornwell, but about what his deeds symbolised to the hearts and minds of a nation.

Amidst all of it, of course, there was a real person. At sixteen-and-a-half, Jack Cornwell was young even in a war that became known for creating a ‘lost generation’ of fallen youth. It was a war fought in large part by everyday people who were not professional combatants, but citizens suddenly called on to fight – to somehow overcome the normal human ‘fight or flight’ reflex. And, often, they found themselves capable of deeds they never imagined might be possible. Did Cornwell simply freeze, a well-understood and natural expression of ‘fight or flight’ reflex? That is plausible and explains what was observed. But there is also the face-value meaning of his later remark to Lawson. Sixteen year old Jack Cornwell was badly wounded, his comrades were dead, the ship devastated. But he had his duty, and he stayed at his post in case there was something he could do.

As always with history, the reality of the moment was likely a mix of factors, and in absence of more information the answer is a discussion, not a statement. But by any measure, Cornwell displayed remarkable bravery that day. On the deck of Chester, for those few minutes when the foredeck was swept by fire, it was natural for Cornwell to be stunned by the concussions of the shell hits, shaken, and scared. He had been aboard just five weeks, had nothing to fall back on, no prior experience to give him succor. But he did his job despite all the odds. Lawson was right to recognise this as a deep display of genuine courage. It was.

Matthew Wright is a professional historian and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society at University College, London. Buy his book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: a gift to Empire (USNI Press 2021) https://www.usni.org/press/books/battlecruiser-new-zealand

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2025

[1] The youngest was Andrew Fitzgibbon (b.1845), who received the VC for deeds at the age of 15 years 100 days. See https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/65707-victoria-cross-youngest-recipient

[2] For example, within my own family I had a great uncle who served at Jutland, aged 19.

[3] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2981965/The-14-year-old-sailors-World-War-Archives-one-three-served-Navy-legal-age.html

[4] https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/us-navy-personnel-in-world-war-ii-service-and-casualty-statistics.html

[5] Anon [Sir John Ernest Hodder Williams], Jack Cornwell: the story of John Travers Cornwell, VC, Boy – 1st Class, Hodder & Stoughton, Toronto 1918, pp. 14-15. Williams was founder of the publishing company.

[6] Ibid, p. 23-43.

[7] Sometimes mis-spelt ‘telepad’, see. e.g. Williams p. 51.

[8] The Royal Navy was not using the 24-hour clock in 1916.

[9] Cited in Williams, pp. 67-39.

[10] Ibid, p. 69.

[11] Matthew Wright, Freyberg: A Life’s Journey, Oratia Books, Auckland 2020, p. 71.

[12] Noted in http://scoutguidehistoricalsociety.com/cornwell.htm

[13] Williams, p. 75.

[14] http://scoutguidehistoricalsociety.com/cornwell.htm

[15] Hansard, Series 5, Vol. 22, 26 July 1916.

[16] —– Battle of Jutland, Official Despatches, HMSO, London 1920, Vice Admiral’s Report, Battle Cruiser Fleet, Encl. No. 9 to Submission 1415/0022, p. 141.Also cited by Williams, pp. 69-70.

[17] https://www.geni.com/people/John-Jack-Cornwell-VC/6000000039457424337

[18] https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/355593/eli-cornwell/

[19] For discussion see Matthew Wright, New Zealand’s Military Heroism, Reed, Auckland 2007, pp. 11-17.

Recent Comments