Based on popular perception, the Yamato class battleships might be associated with a sledgehammer. A tool conveying power, weight, size, and simplicity. Today, the Yamato class are remembered for their large naval guns, tremendous size, and singular purpose of surpassing any battleship then in service. While the Yamato class certainly lived up to these opinions, it does detract from the extremely capable craftsmanship that was lavished upon these battleships. This becomes apparent when one studies the Yamato class armor.

While Japan had three decades of experience with designing dreadnought armor systems, the task of protecting itself against such large and powerful guns as the 46cm (18.1″) then in development (and proceded by other large naval guns that were tested) was a major challenge. The design goal of providing an immunity zone against 46cm shells at a distance of 20km to 30km required Japanese designers to start from scratch.

Vertical Protection

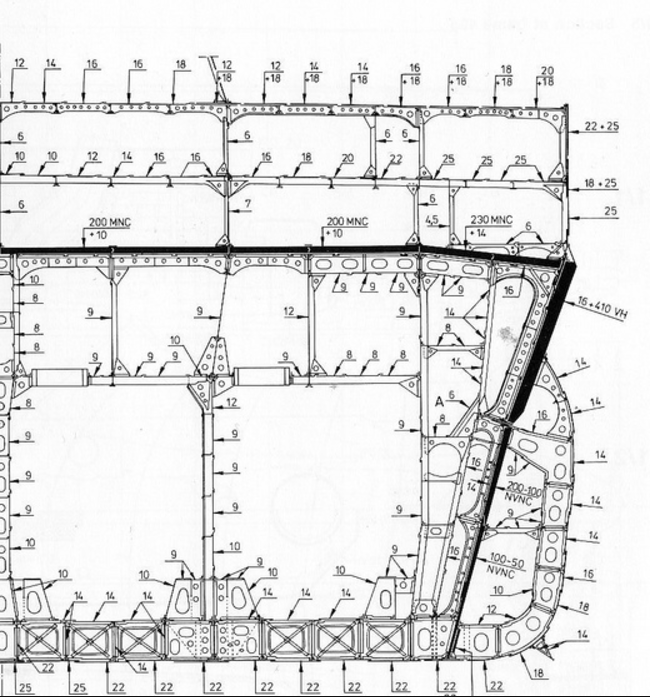

The main armor belt of the Yamato class was 410mm (16.1″) mounted atop 16mm of backing plate, some 105mm (4.1″) greater than the proceeding Nagato class. However, even this was insufficient to withstand 46cm shells at the desired ranges. To compensate, Japanese designers inclined the armor by 20 degrees outwards. Inclining the armor had several advantages. It helped divert some of the momentum away from an incoming shell and it also made it more likely that the shell would bend or even break. Both of these reduced its penetrative power, making it easier for the armor to resist it. The inclination of the belt also increased its relative armor thickness.

Inclined at 20 degrees, the armor saw its relative thickness increased to 436.3mm against a shell approaching from the horizontal. However, this would increase dramatically as the range increased.

For example, the 1,460kg (3,219lb) Type 1 armor-piercing shell could penetrate 494mm of armor at 20km, more than enough to defeat the armor belt. However, at this distance the shell would approach with an angle of descent of 16.5 degrees. Coupled with the inclination of the belt, the shell would strike the armor with an obliquity of 36.5 degrees. This would result in a relative armor thickness of 510mm (20.1″), sufficient to withstand the impact of the Japanese 46cm (18.1″) naval gun. This was before other factors such as shell bending and diverting its momentum came into play, further enhancing the armor. The effects of inclination would continue to greater distances, until it became more likely to strike the armor deck.

Underwater Protection

While it was typical for the armor belt of most battleships to extend for some distance under the waterline, Japanese designers took this a step further. Experiments on the battleship Tosa in June of 1924 showed that large calibre naval shells could carry their momentum for considerable distances underwater.

During testing, a 410mm shell struck the water 25m (82′) short of Tosa. The shell continued the rest of the distance underwater, punching through the hull about 3.3m (11′) under the waterline.

The results of this test were used in the design of the Yamato class a decade later. The lower edge of the main armor belt was joined to a secondary, lower belt with a thickness of 200mm (7.9″). This belt contined all the way to the lower compartments at the bottom of the hull, tapering down to just under 100mm. This lower belt made it near impossible for shells to penetrate the Yamato class underwater. The Imperial Japanese Navy was one of a few navies to identify the threat of underwater shell strikes and one of fewer still that went to such lengths to protect against them.

Unfortunately, the additional protrection to underwater shell strikes came at a corresponding weakness to underwater explosions from mines and torpedoes.

The effects of an underwater explosion interacted with the hull in much different fashion than that of shells. While heavy, rigid armor was needed to withstand a shell, the optimal defense against underwater explosions was thinner, more elastic plates. These plates would absorb some of the pressure wave of an explosion before tearing and allowing the weakened blast to intrude further.

In comparison, the lower belt of the Yamato class was too strong and inflexible. The blast wave, upon reaching the lower belt, was more likely to push the entire belt inward as it refused to bend or tear. As the belt would not break, the force was instead transferred to the weakest part, the joints securing the edges of the belt. The lower belt would instead rupture entire seams of the torpedo protection system. The blast wave was not as absorbed by the belt, meaning it was not weakened as it intruded deeper into the hull.

This was a rather unfortunate development as the Yamato class had a relatively deep torpedo defense system of 5.1m (17′). The system did make use of thinner, elastic torpedo bulkheads to withstand an underwater explosion, but the overall system was severely compromised by the lower belt so far as underwater explosions are concerned. The system was further compromised by the location of the joint where the main armor belt was connected to the lower belt. The depth of this joint was in close proximity to where torpedoes would strike the hull. The concave shape of the joint tended to capture the force of an underwater explosion, diverting most of the energy to this weak point. This could, and did, cause considerable lengths of the joint to fail, allowing extensive flooding.

Even so, this weakness was somewhat countered though extensive internal subdivision. The hull under the armor deck was subdivided into no less than 1,000 watertight compartments, making it very difficult for flooding to spread throughout the hull. In addition, Japanese designers put considerable effort into damage control. The Yamato class had an extensive network of pumps and tanks to counteract the effects of flooding, intended to keep the ship fighting for as long as practically possible.

Horizontal Protection

While the underwater protection of the Yamato class was more complex, the upper armor deck was somewhat simple.

Most navies were making use of multiple layers of armor to protect against long-range shells and bombs (bomb deck, main armor deck, and splinter decks). Japanese designers where no different in that they opted to utilize three armor decks. However, they seemed to place a somewhat greater emphasis on the armor of the main deck, making it somewhat thicker at the expense of the others. The main deck ranged from a thickness of 200mm (7.9″) to 230mm (9″) depending on the location. This was a byproduct of having to resist 46cm shells out to 30km. While multiple layers of armor were effective at resisting bombs, it was determined that a singular layer of thick armor performed better against larger calibre naval guns. Even so, the main armor deck was calculated to be resistant against a 1,000kg aerial bomb.

Above the main armor deck was the weather deck, crossing the top of the hull. The armor plates here ranged from 30 to 50mm. This was sufficient to protect the upper hull against light bombs up to 250kg as well as strafing attacks by aircraft. The third layer of armor was found under the main armor deck. This was a 9mm thick splinter deck, intended to catch any splinters or spalling produced by the main deck.

Added complexity

Without a doubt, this extensive use of such thick armor plates would result in tremendous weights. However, the prodigious size of the Yamato class belies the considerable effort Japanese designers put into saving weight.

Japan was able to reduce the overall tonnage of the Yamato class by using large portions of the armor as structural components. Typically, most warships utilize a framework of longitudinal and traverse bulkheads. The hull frame was erected and plated over, forming a complete hull. The armor was then simply attached to this hull. For the Yamato class, designers integrated the armor into the hull, making it a part of the ship’s structural integrity and saving weight be removing the need for certain bulkheads.

There were downsides to this design feature. Notably the hulls had to be launched with a majority of their armor installed rather than the traditional process of launching the complete hull and then attaching the armor once afloat. This made it so the Yamato class were extremely heavy when launched, so much so that after the first ships were launched by traditional slipway it was decided that all future ships should he built inside of drydocks.

However, while the integrated armor made the Yamato class more expensive and complex to build, it did make them significantly lighter than they would have been had they been built by more conventional means. An impressive achievement considering the class is most known for being the largest and heaviest battleships ever built.

Final Thoughts

So far as armor protection goes, the Yamato class tend to be remembered for the wrong reasons. They are often unfairly compared with their predecessors, leading some to think that their armor antiquated. Their sinking by aircraft, even with lighter bombs and torpedoes, tends to make them seem as failures.

In reality, the armor system of the Yamato class was a quantum leap in armor theory and design. Japanese designers leveraged all of their knowledge to produce an armor system that was completely different from earlier designs. Through extensive testing, they further honed it into a system that was unique among Japanese ships as well as contemporaries. Overall, the system was well-thought out, well-tested, and very capable.

The loss of Yamato and Musashi to air attack does little to diminish this achievement. Though they were lost to a massed attack by aircraft, it’s unlikely any other battleship would have fared better in the same situation. The highest quality armor system in the world would do little against such overwhelming quantity of bombs and torpedoes.

Given the time of their design and what was known about naval combat at the time, the Yamato class were truly remarkable achievements.

Recent Comments