America’s only battlecruisers,[1] the Lexington class, emerged from ideas flowing through the Naval War College, General Board and other US Navy circles before and during the First World War.[2] As we saw in the previous article, this thinking finally came together with mid-1916 legislation designed to give the United States a navy the equal of any other. That authorised, but did not fund, six battlecruisers as part of a massive multi-year expansion programme.[3]

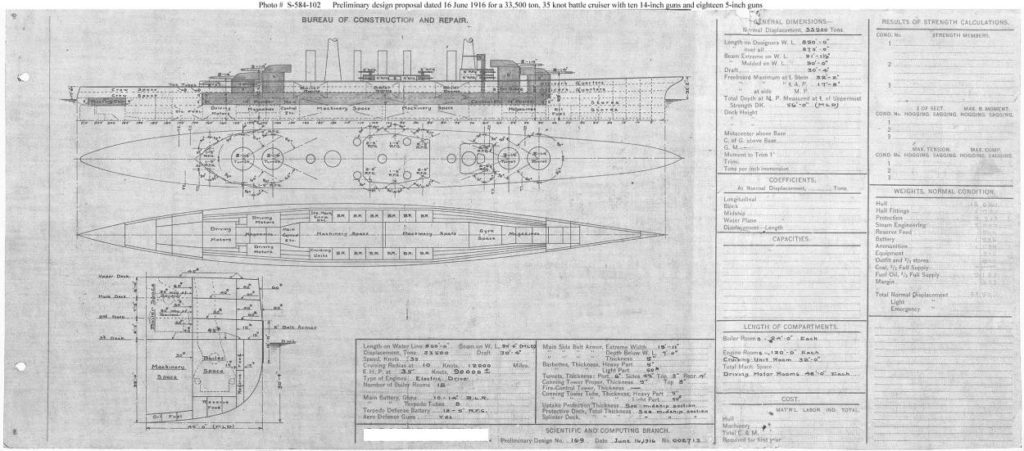

Work had been under way on sketch designs for some time before the naval act was passed, largely to guide the legislation.[4] Plans for battlecruisers had been developed as part of the ‘scout cruiser’ theme explored during 1915, and in August the General Board requested the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BC&R) to explore further variations of speed and displacement. One outcome was Design 145 of some 35,500 tons.[5] The characteristics were confirmed on 13 October, anchoring the design process, and by mid-1916 the BC&R was projecting ships with ten 14-inch/50 calibre guns and a speed of 35 knots.[6]

This helped inform the legislation, which went through the enactment process during the middle months of the year. However, this all took place to the backdrop of the First World War and the lessons the British were learning from war experience. These had a clear influence on the final Lexington design – first in terms of timing, then in terms of what happened.

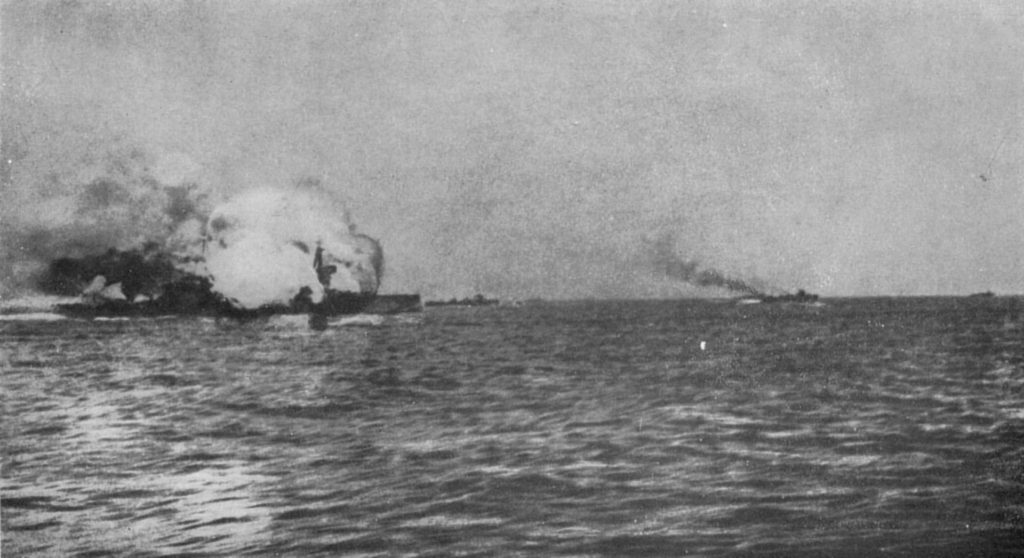

By 1916 the war had revealed issues with a range of operational and design practises in the Royal Navy, underscored by the loss of three battlecruisers and one armoured cruiser to devastating magazine explosions at Jutland, with the loss of 4212 officers and men between them.[7] This was a human tragedy of massive scale. But it was also a worry for the fleet. Were all ships vulnerable? The Commander in Chief of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, initially reported that the cause was ‘the indifferent armour protection of our battlecruisers’.[8] That reflected pre-war criticism of their protection. However, he also set up a committee to look into this issue.[9] The main problem was that the wrecks could not be examined, and there were few survivors to question.[10]

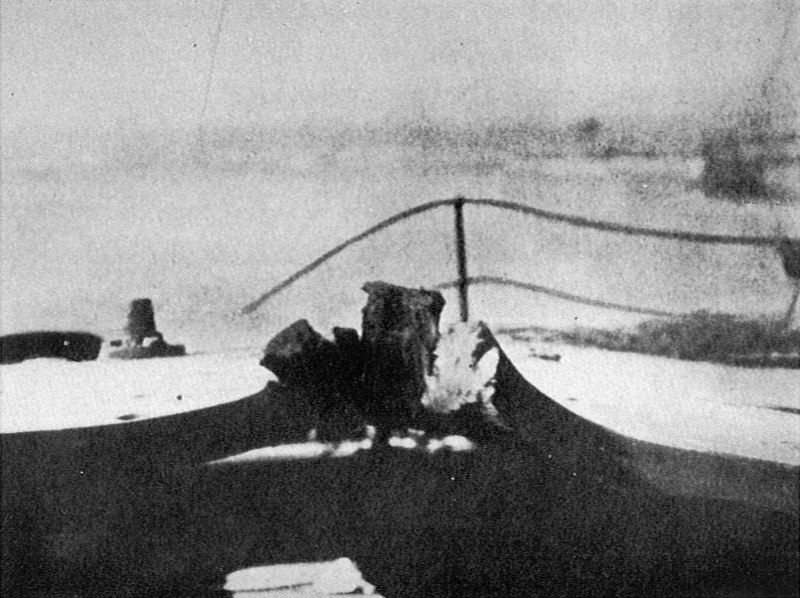

However – while accepting that the specific fate of each ship was slightly different – the committee came up with two general issues. The most likely cause, they found, was that faulty munitions handling combined with cordite propellant left the ammunition passages vulnerable to fire. This was a result of the ‘hail of fire’ doctrine, by which shells and cordite were supplied as quickly as possible. Crews were bypassing safety procedures, creating open paths from the magazine to the turret, often littered with cordite charges.[11] If the turret was hit, there was a risk of fire spreading into the magazines. The British had come within a whisker of losing Lion to that cause during the battle,[12] and New Zealand had barely dodged a similar fate when an 11-inch shell broke the 9-inch glacis armour of X-turret, filling the turret with fumes, but without causing a fire.[13]

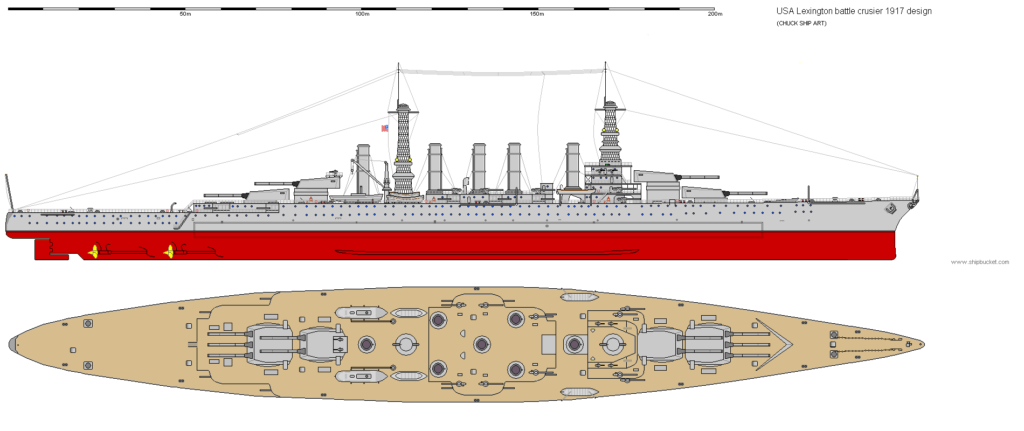

This point was soon known in United States naval circles where the Chief of the Bureau of Ordinance, Rear-Admiral Joseph Strauss, told Congress that the Lexingtons did not share that weakness.[14] In this he was reflecting general US Navy opinion of the day.[15] As a result, once the bill became law, the Secretary of the Navy authorised Design 169 for further development on 29 August.[16] What emerged was a ‘classic’ battlecruiser in which speed and fire-power were prioritised over protection. While the planned armoured belt was of impressive extent, it was only 5.75 inches thick, and on paper, the ship’s own main armament was capable of penetrating that at ranges out to 35,000 yards.[17] The main problem, however, was that the required speed demanded a propulsion plant generating 180,000 horsepower, and a proportion of the 24 boilers had to sit above the armoured deck.[18] This left them vulnerable to shellfire, although the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BC&R) tried to sell it as an advantage: the boilers were not at risk from torpedoes.

While the the BC&R were working on that design, however, debate continued across the Atlantic over the lessons of Jutland. The issue confronting the Royal Navy was the second possible cause that Jellicoe’s committee had found behind the battlecruiser explosions: the possibility that splinters from shells bursting inside the ship had penetrated either the ammunition hoists or the magazines. The hoist issue could be fixed by adding flash-doors and tightening munitions procedure. The magazine problem, however, required more armour. While the Committee felt this cause was demonstrably true only for Invincible,[19] the point played to the pre-war notion – reflected in Jellicoe’s first report to the Admiralty[20] – that battlecruiser armour was inadequate. Jellicoe and Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty reported these findings to the Admiralty on 25 June.[21]

The debate that followed within the Admiralty and British naval circles had a decisive effect on the design of Lexington. However, it took time to play out, and its nature reflected the way that shells were understood to affect complex structures such as warships. As a result, the debate was complex, further infused with the power-balances within the Royal Navy’s sub-culture.

There was no question about the munitions handling issue, however, and the death toll gave it a political tone.[22] The British public were reeling from ongoing casualties on the Western Front, compounded the week after Jellicoe and Beatty reported to the Admiralty, when the Somme offensive opened with the worst one-day casualties the British army had ever suffered.[23] The possibility that the Jutland losses had likely been avoidable became even more unpalatable.

It was therefore in the interests of officers such as Beatty to draw attention to splinter penetration.[24] However, the argument stirred up the issue of battlecruiser armour, and opinion differed.[25] One extreme was summed up by Rear-Admiral Osmond de Beauviour Brock, who felt the losses were due to German shells penetrating the magazines.[26] The opposite was summed up by the Third Sea Lord and Controller, Rear-Admiral Sir Frederick Charles Tudor Tudor,[27] who thought lax munitions procedures the sole cause.[28] This last guided the initial Admiralty line – fuelled by D’Eyncourt.[29] An initial request from Jellicoe and Beatty to improve munitions procedures, add flash protection, and improve magazine roof armour was turned down.[30]

This debate – which also reflected ‘back protection’ by Jellicoe and D’Eyncourt[31] – did not reduce the fact that magazine penetration by shell splinters – whether a direct cause or not at Jutland – had still been identified as a risk. It was intensified by the fact that the British believed the Germans had 15-inch gunned battlecruisers under construction.[32] The British were also improving their own armour-piercing shells[33] – another Jutland lesson – and had to assume the Germans would do the same.

That threw focus on new construction. Two battlecruisers with relatively light armour were about to join the fleet,[34] three ‘large light cruisers’ with minimal protection were under construction, and a class of four battlecruisers with better but still modest protection, by comparison with battleships, were about to be built. The first of the four, HMS Hood, was actually laid down on the day Jutland was primarily fought.[35] Edward Attwood’s design embodied multiple innovations, including sloped belt armour.[36] However, questions flowing from the battle prompted the Admiralty to halt construction.

D’Eyncourt examined damage to Warspite, Lion, Tiger and Princess Royal, concluding from his observations that shells would always defeat armour, but that splinter protection around the magazines would protect them from shells bursting inside a ship, after the belt or deck was penetrated. He considered this was also true for the battlecruisers under construction.[37]

That stood against opinion in the fleet, and Beatty formed a committee to look into Hood’s design, which – inevitably – recommended thicker armour. The conclusion spurred debate within the Admiralty, followed by a conference with Jellicoe. After various gyrations D’Eyncourt backed down and modified Hood’s armour, which the Board of Admiralty approved on 2 October.[38] Jellicoe talked to Tudor about it on 12 October, finding Hood now had the belt armour he wanted.[39] But he had concerns about magazine protection, arguing it with D’Eyncourt;[40] and there were ongoing modifications into 1917, even as construction progressed.[41] In many respects the eventual design brought to reality the ‘fusion’ warship envisaged by the British as early as 1906-07.[42] As D’Eyncourt remarked to Jellicoe, Hood was better protected than any known warship of the day.[43] The Admiralty – prompted by Tudor[44] – nevertheless classified her as a battlecruiser.[45]

All this had effect on the final Lexington design. However, it took time for the ideas to arrive in Washington. One historian has argued that the General Board had authorized vessels that went against wartime experience.[46] But in fact the late August 1916 decision to detail the sketch design was in accord with prevailing US Navy doctrine.[47] The Lexingtons had the speed to control the range – to their advantage. Nor did US designers have to submit their ideas to the British for approval; any lessons were always going to be absorbed and understood through American expertise and decision-making processes. Furthermore, while personal relations between US and British naval officers and officials had long been warm,[48] the BC&R was not privy to internal British discussions. They already knew that Lexington did not share the munitions-handling process or flash-propagation issues of the British battlecruisers at Jutland. The 29 August decision to proceed on the basis of Design 169 was, therefore, reasonable on many levels.[49]

None of this was obvious to the American public: in December 1916 the Scientific American described the Lexingtons as ‘stupendous warships’ with a combination of ‘size, speed and power’ that ‘must be considered to be the most novel and sensational’ since Dreadnought. But, the magazine admitted, they did not know about Lexington’s protection.[50]

Early in 1917 the Bureau of Ordnance proposed 16- instead of 14-inch guns for the battlecruisers.[51] The re-design also embodied newer propulsion technology, which was able to reduce the number of boilers and funnels while still providing power for 35 knots. However, armour was unchanged, because to alter it affected the longditudinal strength of the hull. At the time, designers made calculations manually, aided only with slide-rules and printed logarithmic tables. Developing the figures for a complex structure such as a warship was a lengthy task, particularly because the major components were inter-related. Schedules often did not permit re-calculation.

The result took Lexington further away from the rule-of-thumb principle that a balanced warship should have protection against its own main armament. Yet, in other ways, it enhanced the design from the perspective of the expected tactical role. The 16-inch/50 calibre gun had excellent performance,[52] and was clearly superior to the earlier 14-inch/50.[53]

Lexington was contracted with the Fore River Ship-Building Corporation on 26 April 1917,[54] and Saratoga with the New York Shipbuilding Corporation on 5 May.[55] Contracts for the other four were also organised. Then in July the programme was suspended in consequence of the US entry into the war.[56] That gave the BC&R time to further develop the designs, driven in part by changes in thinking within US naval circles, further shaped as the details of the lessons learned by the Royal Navy arrived during early 1918 and were absorbed.

We shall look at that – and the ultimate iteration of the Lexington – in the final part of this series. Meanwhile, for more on battlecruisers, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: A Gift to Empire. Click to buy.

About the author: Matthew Wright is a professional historian who has been extensively published by Penguin Random House, has written many academic papers, and is best known for his international contribution to military and naval history. Many of his books have been used as university texts. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society at University College, London. Visit him online at www.matthewwright.net

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2020

[1] The US Navy designation for battlecruiser was CC (‘Capital Cruiser’). The Alaska class of the Second World War were designated ‘CB’, ie: large cruiser; see Ian Sturton (ed) Conway’s All The World’s Battleships, Conway Maritime Press, London 1987, p. 184.

[2] See https://www.navygeneralboard.com/the-origins-of-the-american-battlecruiser-part-2-the-road-to-the-lexington/

[3] Robert C. Stern, The Battleship Holiday, Seaforth, Barnsley 2017, p. 86.

[4] See https://www.navygeneralboard.com/the-origins-of-the-american-battlecruiser-part-2-the-road-to-the-lexington/

[5] http://www.shipscribe.com/styles/S-584/images/s-file/s584082c.htm

[6] Tony Gibbons, The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers, Salamander, London 1983, p.234.

[7] Nigel Steel and Peter Hart, Jutland 1916: death in the grey wastes, Cassell, London 2004, p.438

[8] A. Temple Patterson (ed), The Jellicoe Papers, Navy Records Society, London 1966, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 18 June 1916, p. 286.

[9] Stern, p. 75.

[10] Casualty lists for HMS Invincible are here: https://www.northeastmedals.co.uk/britishguide/jutland/hms_invincible_casualty_list_1916.htm , for HMS Indefatigable here: https://www.northeastmedals.co.uk/britishguide/jutland/hms_indefatigable_casualty_list_1916.htm , for HMS Queen Mary here: https://www.northeastmedals.co.uk/britishguide/jutland/hms_queen_mary_casualty_list_1916.htm , and for HMS Defence here: https://www.northeastmedals.co.uk/britishguide/jutland/hms_defence_casualty_list_1916.htm

[11] Euan MacFarlane, ‘British Naval Innovation and Performance Before and During the First World War: The 1916 Sinking of the HMS Invincible’, BA (Hons) dissertation, University of Northumbria, 2015, pp. 27-29.

[12] Steel and Hart, pp. 114-115.

[13] Ibid, p. 115. The broken armour is held by the Royal New Zealand Navy Museum at Torpedo Bay, Devonport.

[14] Norman Friedman ‘How promise turned to disappointment’, Naval History Magazine, Vol. 30, No. 4, August 2016.

[15] Ryan Alexander Peeks, ‘The Cavalry of the Fleet: Organisation, doctrine and battlecruisers in the United States and the United Kingdom, 1904-22, PhD thesis, University of North Carolina, 2015, p.322.

[16] http://www.shipscribe.com/styles/S-584/images/s-file/s584102c.htm

[17] http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_14-50_mk11.php

[18] Kermit Bonner, Final Voyages, Turner Publishing Company, 1996, p. 189.

[19] R. A. Burt, British Battleships of World War One, Seaforth, Barnsley 2012, p. 111.

[20] A. Temple Patterson (ed), The Jellicoe Papers, Navy Records Society, London 1966, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe to the Secretary of the Admiralty, 18 June 1916, p. 286.

[21] Stern, p. 75.

[22] For summary see Nathanial G. Ott, ‘Battlecruisers at Jutland: A Comparative Analysis of British and German Warship Design and its Impact on the Naval War’, Senior Honors Thesis, Ohio State University, 2010, pp 28-29.

[23] Andrew MacDonald, First Day of the Somme, HarperCollins, Auckland, 2016, pp. 359-360.

[24] Ott, p. 31

[25] Modern opinion is that armour issues cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor, see, e.g. William Jurens, The Loss of HMS Hood: a re-examination, http://www.navweaps.com/index_inro/INRO_Hood.php

[26] McFarlane, p. 29.

[27] His middle and last names were the same: http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Frederick_Charles_Tudor_Tudor

[28] Stern, p. 75.

[29] MacFarlane, p. 32.

[30] Stern, p. 75.

[31] McFarlane, p. 31.

[32] Friedman, The British Battleship, p. 187.

[33] Norman Friedman, Fighting the Great War at Sea, Seaforth, Barnsley, 2014 p. 178.

[34] HMS Repulse and HMS Renown, both with a 6-inch belt.

[35] Sturton (ed), p. 90.

[36] See, e.g. Friedman, The British Battleship, p.185.

[37] Friedman, The British Battleship, p. 195.

[38] Ibid, p. 186-187.

[39] Ibid, p. 186.

[40] ADM 1/9210, Jellicoe to D’Eyncourt, 7 November 1916.

[41] For details see Friedman, The British Battleship, pp. 185-187.

[42] Friedman, The British Battleship, p. 96.

[43] ADM 1/9210, D’Eyncourt to Jellicoe, 9 December 1916.

[44] ADM 1/9209, ‘Design of Battle-Cruisers with Increased Protection’; see also Friedman, The British Battleship, p. 186.

[45] See, e.g. Sturton (ed), p. 90.

[46] Peeks, p. 249.

[47] Trent Hone, ‘Building a doctrine: U.S. Naval Tactics and Battle Plans in the Inter-War period’, International Journal of Naval History, Vol . 1, No. 2, October 2002, p. 15.

[48] See, e.g. Rear-Admiral William S. Sims to Jellicoe, 13 April 1916, The Jellicoe Papers, p. 235.

[49] See note 15.

[50] https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/anecdotes-from-the-archive/battle-cruiser-a-flawed-ship-design-from-1916/

[51] Ryan Peeks, ‘Battlecruisers in the United States and the United Kingdom 1902-1922’, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/battlecruisers-in-the-united-states-and-the-united-kingdom-1902-1922.html

[52] For details see http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_16-50_mk2.php

[53] For details see http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNUS_14-50_mk11.php

[54] Date given in Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1930, United States Government Printing Office, Washington 1931, p. 86. Note that 27 April is given in source per n. 56, below.

[55] United States Congress, House Committee on Naval Affairs, Sundry Legislation Affecting the Naval Establishment, 1924-25, Government Printing office, Washington 1925, p. 157.

[56] Stern, p. 86.

Recent Comments