The unprecedented cold that swept parts of the United States in early 2019 could be called ‘brass monkey weather’, though with the temperatures reported, that might be an understatement. According to legend, the term – in full, ‘cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey’ is neither nonsense, nor scatological. What’s more, it supposedly has a naval origin, reputedly one of many colourful turns of phrase that have crept into the English language from military life at sea.

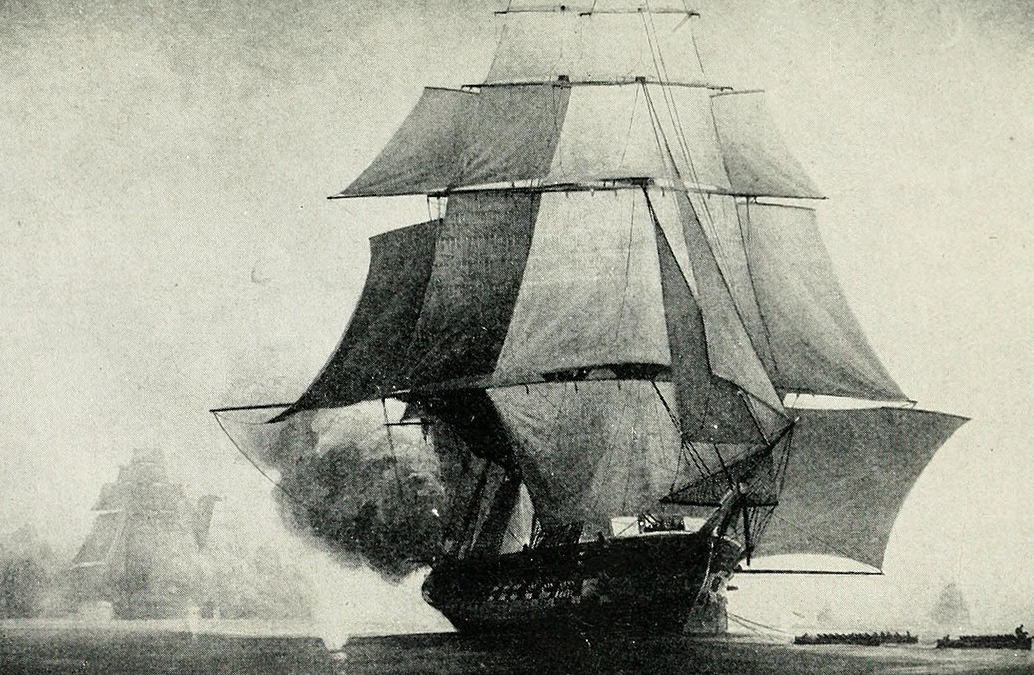

In a certain sense that seems plausible. Naval history has given English some wonderful phrases – everything from the word ‘grog’ (liquor), to ‘hand over fist’, to ‘loose cannon’. This last was a risk during the age of sail if a cannon’s restraining rope broke and it rolled about the deck in heavy seas, a danger to all around. The term entered common English usage as a metaphor, apparently, because a United States President, Theodore Roosevelt, once remarked that he didn’t want to be remembered as if he were a loose cannon.

The big one, of course, is ‘cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey’, often rendered as ‘brass monkey weather’. However, its supposed naval explanation is dodgy. According to mythology, it came about because in the age of sail, cannon balls were apparently stored on deck in neat pyramids, contained by a brass tray supposedly known as a monkey. When the temperature dropped too far, apparently, the coefficient of expansion in the brass differed from that of the iron shot – so hey presto, the balls were pushed off the tray. It all sounded very tidy and clever, but unfortunately none of it was even slightly true, and there is some evidence that this ‘explanation’ originated as recently as the 1980s.[1]

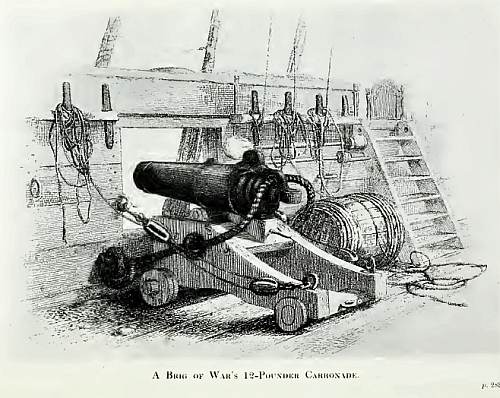

It certainly isn’t hard to refute. The physics of metallurgy alone is a clue: the real difference in coefficient of expansion between brass and iron isn’t anywhere near enough to act as the myth suggests. Besides which, in the age of sail there was no such thing as a ‘brass monkey’ to hold what in naval parlance was actually called ‘shot’. Nor was shot stored in pyramidal stacks on deck anyhow, and for good reason. Ship movement in any reasonably heavy weather would have been enough to dislodge it, causing the shot to roll about, probably joining that cannon mentioned earlier. The reality was that shot – up to 120 tons of it in a three-deck ‘line-of-battle’ ship – was kept in ‘shot lockers’.[2] When it was needed for firing, it was brought up and put in a ‘shot garland’, a plank with cannon-ball sized holes cut in it.

So where does ‘cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey’ come from? This has been extensively discussed.[3] However, it’s unlikely to be naval. In a naval (and general nautical) sense, the word ‘monkey’ has had many uses, not all of them still current. They include ‘monkey boat’ (a narrow vessel used on canals) and ‘monkey block’ (part of the rigging system). Some of the others include:

1. ‘Monkey island’ – the uppermost accessible part of the vessel, usually applied to merchant ships.[4]

2. ‘Monkey jacket’ – a style of uniform jacket common during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Admiral Sir David Beatty typically wore one with six instead of eight buttons.[5]

3. ‘Monkey’ or ‘munkey’ – a type of naval cannon from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, usually made of brass, also known as a ‘drake’ or a ‘dog’.

4. ‘Powder monkey’ – the sailor bringing powder to the guns, sometimes also known as the ‘powder boy’. The term survived in the US Navy at least into the 1860s.[6]

The reality is that nobody knows exactly how the term actually originated, or what it really referred to: sometimes, figures of speech can gain a life of their own, well removed from any literal origin. It seems to have been in use by the mid-nineteenth century, in many variants. One of the earliest references is by US author Herman Melville, who used something like it in his 1847 novel Ormoo.[7] But where it originally came from remains unclear. There is a possibility that it referred to the traditional pawnbroker sign, with its three spheres; but this is not decisively proven. In all probability, like so much about the English language and its phrases, the specifics of its origin in social usage are sufficiently diffuse, and the records sufficiently sparse, that they cannot be definitively pinned to any one moment or place.

One point seems certain: for all the mystery around its etymology, we can be reasonably sure that it is not a naval term. And yet we can learn a few interesting things about naval matters along that road of discovery.

For more on naval history, check out my book The Battlecruiser New Zealand: a Gift to Empire. Click to buy.

Copyright © Matthew Wright 2019

[1] http://seatalk.blogspot.com/2005/12/garlands-and-brass-monkeys.html

[2] Geoffrey Bennett, The Battle of Trafalgar, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Barnsley 2004, p. 28.

[3] For example, https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/alt.usage.english/A70ArTxdfGw%5B1-25%5D

[4] https://www.marineinsight.com/marine-navigation/what-is-monkey-island-on-ships/

[5] https://www.geni.com/people/Admiral-of-the-Fleet-David-Beatty-1st-Earl-Beatty-GCB-OM-GCVO-DSO-PC/6000000009580442815

[6] https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/sail-armament.htm

[7] https://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/cold-enough-to-freeze-the-balls-off-a-brass-monkey.html

Trackbacks/Pingbacks