It’s not often that a city’s memorial to a warship is larger than the ship itself. Or that the ship’s bell continues to be rung in that city to this day, honouring the way the navy came to the rescue when tragedy unfolded. But that’s true in Napier, New Zealand, where a semi-circular memorial – the Veronica Sun Bay – stands on the foreshore in honour of the sloop HMS Veronica. It’s slightly further around than Veronica was long, and it bears Veronica’s name-plate and a place to hang her bell for ceremonial occasions. The bell is held in the local museum, but is brought out and rung to mark key occasions several times a year – especially on 3 February, the anniversary of the day disaster struck the city in 1931. The memorial has been an iconic part of the city-scape since it was dedicated in 1937, so important to Napier that when the original was found to be crumbling in the late 1980s, a new one was built to the original design, funded by public subscription.

HMS Veronica was an Acacia class sloop, completed in August 1915 with a displacement of around 1,200 tons, and a length of some 262 feet.[1] She joined the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy in September 1920 and was a familiar sight around New Zealand ports for fourteen years.

Around 6 am on the morning of 3 February 1931, Veronica arrived in the Napier roadstead for a scheduled visit and anchored, awaiting the arrival of the harbour-master, H. Whyte-Parsons. He boarded around 7 am and by 8 they were secured alongside the wharf at West Quay, in the inner harbour, a little south of where Morgan first intended to moor. Morgan’s first engagements ashore were not until mid-afternoon; they had arrived early and taken advantage of the tide to enter.

Whyte-Parsons recalled that around 10.45 am they were both in Morgan’s cabin.[2] Morgan’s report of 11 February indicated he was on the quarterdeck. Either way, at 10.47 am the ship was abruptly ‘flung about’ by a sudden and very violent earthquake that tore across the district in two great spams, for three minutes. Morgan saw ‘the road and wharf heaving about, the storehouses opposite swaying in all directions whilst others were crashing to the ground in ruins.’[3] Five of the six hawsers connecting the sloop to the wharf broke, and the quayside aft – where Morgan had originally intended to moor – collapsed.[4]

It was the largest earthquake to strike a major New Zealand centre since the Wellington quakes of 1848 and 1855. At the time, Charles Richter calculated it was 7.9 on his intensity scale; later analysis put it at 7.8 on the newer moment magnitude scale. It laid waste to a wide swathe of the North Island’s east coast, particularly the main centres of Napier and Hastings; there was damage as far north as Gisborne and as far south as Wanganui. The shock was felt across the country. Even in Christchurch, hundreds of kilometres south, it set lamps swaying.[5]

None of the wider devastation was obvious from the Veronica as she swung on her remaining cable – the spring – into the harbour.[6] But it was clear disaster had struck; fires were already burning in the devastated buildings ashore. First priority was securing the ship, but Morgan took a moment to raise the alarm, signalling the Devonport naval base in Auckland by morse at 10.54 am, just four minutes after the shaking subsided. They now realised water was rushing from the inner harbour. Veronica was not merely in danger of coming adrift; the harbour was shallow at the best of times and she faced grounding and canting over. The crew hauled the ship back alongside the wharf, and Morgan had the kedge anchor put ashore ‘so as to assist to hold the ship upright if she commenced to fall over to starboard’. Water was pouring from the harbour ‘like a mill race’ by this time, so he ordered the ‘port tanks flooded to list the ship against the wharf’.[7] It was 11.40 – some 50 minutes or so after the disaster – before Veronica was safe. Aftershocks rattled the area and Morgan had some concern that the quayside might yet collapse on them, but there was nothing he could do about it.

The gravity of what had happened ashore in the port district, Ahuriri, was clear; the area was in ruins. The fate of the main town – on the other side of Napier hill – could only be imagined. As soon as the ship was safe, Morgan called for volunteers to render assistance. The entire crew stepped up; he had to get his officers to select men. Five parties eventually went ashore, joined by seamen from two freighters in the roadstead who put themselves under Morgan’s command.

Morgan’s first emergency signal arrived in Auckland just as the two cruisers of the New Zealand Naval Division, HMS Dunedin and HMS Diomede, had steam up and were readying to depart for joint exercises with the Royal Australian Navy. When a second signal from Morgan at 11.27 revealed the ‘precariousness of the situation’ in Napier,[8] Commodore Geoffrey Blake cancelled the manoeuvers and got in contact with Dr C. E. Maguire, superintendent of Auckland hospital.[9] Eleven doctors — including Dr H. L. Gould, the Assistant Medical Superintendent — and seventeen nurses arrived within ninety minutes. They were joined by the Rev. G. T. Robson, M. C., chaplain of the shore base HMS Philomel. Surgical and medical stores, an X-ray plant provided by Philips Lamps, 54 stretchers, 5 marquees, 34 tents, 400 blankets, 125 beds, 200 ground sheets, 80 shovels and 21 picks were assembled on the dockside by 2.00 p.m. and loaded within half an hour. The cruisers immediately put to sea, working up to 24 knots and rounding North Head by 3.00 p.m.[10]

Few on board slept as the cruisers dashed for the disaster zone. Crews were divided into rescue parties and given training in stretcher-bearing and first aid.[11] Galley hands worked to bake bread, while others set up the X-ray machinery in the torpedo flat.[12] They reached Napier at dawn on 4 February, slowed on reports of shoaling, and worked their way in, finally anchoring off the harbour entrance.

Napier’s town centre was still burning as the ships arrived; the city was only saved from a greater disaster by a herculean effort on the part of the fire brigade.[13] The death toll was officially given, later, at 256:[14] at the time, as fires raged and rescuers scrabbled to pull people clear, there were fears that over 300 had died. Over 400 were seriously injured, and thousands more hurt to some extent or another. Devastation extended across the entire district.

Although civilians ashore were rallying, and an army convoy arrived at virtually the same time as the cruisers, the Navy made an enormous contribution over the next few days. The Marines set up headquarters at the Byron street Police Station under Royal Marine Captain Hardy Spicer of HMS Dunedin.

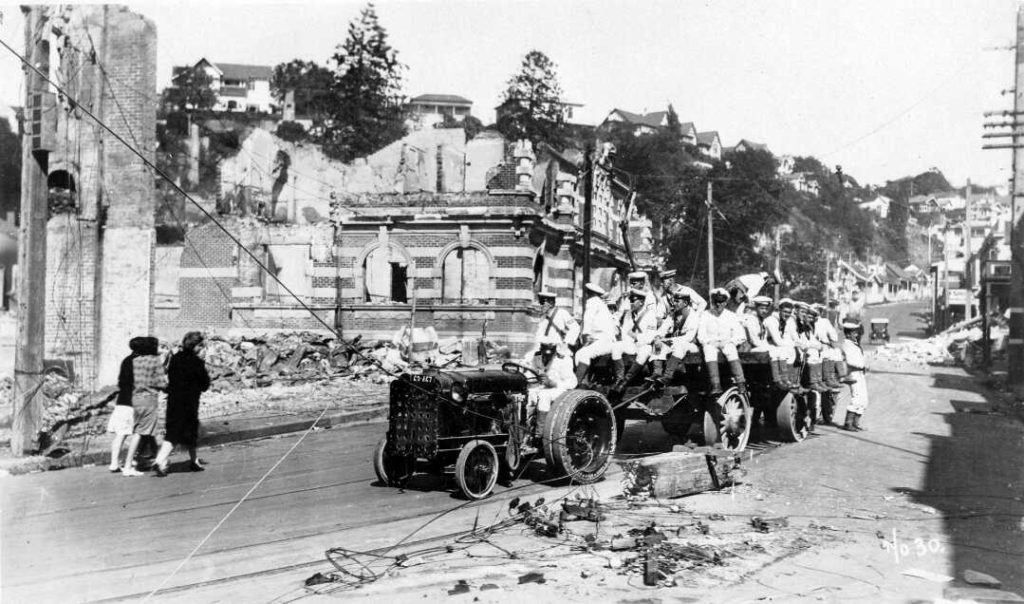

Sailors at the bottom of Shakespeare Road, Napier – likely being transported from their ship, Veronica, on the other side of the hill. MS-Papers-2418-5-02. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22889790

‘The first two days were the worst,’ Spicer later recalled ‘for the men had no sleep whatever.’ Royal Marine Captain J. C. Westall of the Diomede later explained to reporters that they ‘acted as firemen, took part in demolition work, cooked meals for refugees, were food distributors, water carriers, tractor drivers, policemen, searched for the dead and carried bodies to the morgues, carried out sanitation work, and even acted as nurses in the hospitals.’[15] The work took its toll on them emotionally. Quake survivor Mary Hunter was helped a few days afterwards by a marine who was ‘really shaking with horror.’[16] Another sailor told a survivor he had ‘never seen such appalling sights.’[17]

The sailors were ubiquitous across Napier and the inland districts through the next few weeks – and it was small wonder, afterwards, that somebody remarked ‘thank God for the Navy!’[18]

The role the navy played in the days after the quake was especially poignant in Napier, which was the hardest hit centre, and established an enduring bond between city and service. Morgan and his crew, particularly, became national heroes. Morgan was made a CMG in recognition, and the Auckland Navy League raised funds for a trophy – the Veronica Cup – to commemorate the work done by the navy in Hawke’s Bay.[19] A Napier street was later named after Morgan, and another after his ship.

The most enduring recognition of Veronica’s role remains the memorial on the foreshore, begun three years after the quake, and dedicated in 1937 when the First Sea Lord donated the ship’s bell and name-plate to Napier.

Napier was rebuilt during the 1930s in modernist styles, intentionally taking inspiration from Santa Barbara. Today the Veronica Sun Bay stands in testimony to the time when the navy came to the rescue. Tourists walk in and around it, scarcely looking at the memorial plaques that underscore the story of humanity, heroism and duty in the face of what remains the most lethal natural disaster ever experienced in New Zealand.[20]

For more on that earthquake and the role of the navy, check out my book Living On Shaky Ground (Bateman Books, 2020) – click to buy.

[1] E. H. H. Archibald, The Metal Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy, 1860-1970, Blandford, London 1971, p.150.

[2] Hawke’s Bay — Before and After, p. 85

[3] http://navymuseum.co.nz/1919-1939-rop-for-hms-veronica-11-february-1931-napier-earthquake/

[4] New Zealand Herald, 06/02/1931

[5] Matthew Wright, Quake – Hawke’s Bay 1931, Reed, Auckland 2001, 2006 reprint, pp. 31-37.

[6] http://navymuseum.co.nz/1919-1939-rop-for-hms-veronica-11-february-1931-napier-earthquake/

[7] http://navymuseum.co.nz/1919-1939-rop-for-hms-veronica-11-february-1931-napier-earthquake/

[8] Hawke’s Bay — Before and After, p. 149.

[9] New Zealand Herald, 04/02/1931.

[10] Hawke’s Bay — Before and After, p. 84.

[11] New Zealand Herald, 04/02/1931

[12] New Zealand Herald, 06/02/1931

[13] Wright, Quake – Hawke’s Bay 1931, pp. 60-64.

[14] Ibid, pp. 101-102. But note that this figure does not tally with the 258 listed on the mass grave site; and has since been questioned.

[15] Hawke’s Bay — Before and After, p. 86.

[16] Hawke’s Bay Museum archive, Earthquake Personal Reminiscences, Mary Hunter memoir.

[17] Hawke’s Bay — Before and After, p. 77.

[18] Attributed to a Napier hill resident, 4 February 1931. Hawke’s Bay — Before and After, p.84. See also Minhinnick cartoon caption, New Zealand Herald, 09/02/1931.

[19] Evening Post, 6 June 1931.

[20] The official death toll was 256; this has been disputed since but the question cannot be answered from available records. The variation is thought to be small (circa 253-259).

Recent Comments